Welcome to the Feminist Accountability Map

...which tracks the progress of countries in Asia and the Pacific against its commitments to women's human rights and Development Justice.

1.Desktop OR 2.Tablet

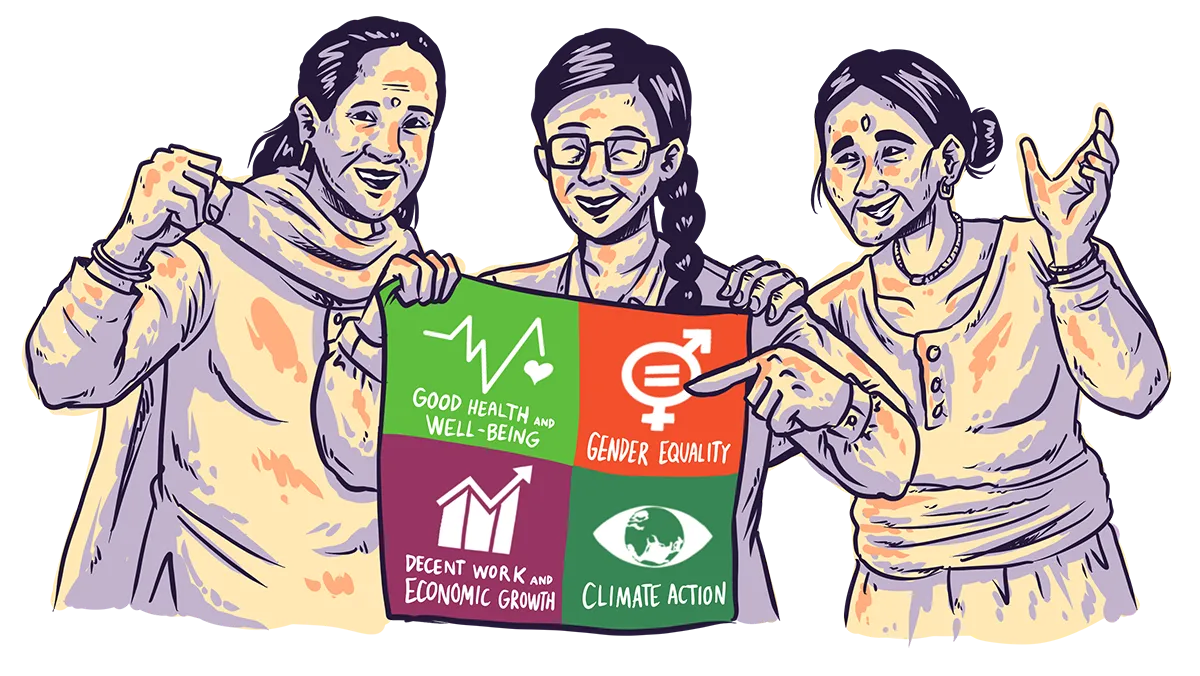

About The Feminist Accountability Map

The Feminist Accountability Map was developed by APWLD based on the research and work of its members and partners in Asia and the Pacific to highlight issues, gaps in accountability, and women's voices in the pursuit of women's human rights and Development Justice. It combines country-specific reports and external resources to highlight government failures or achievements in meeting human rights commitments and expose barriers in meeting the same.

How to use the Map

Subregional Analysis

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia  South Asia

South Asia

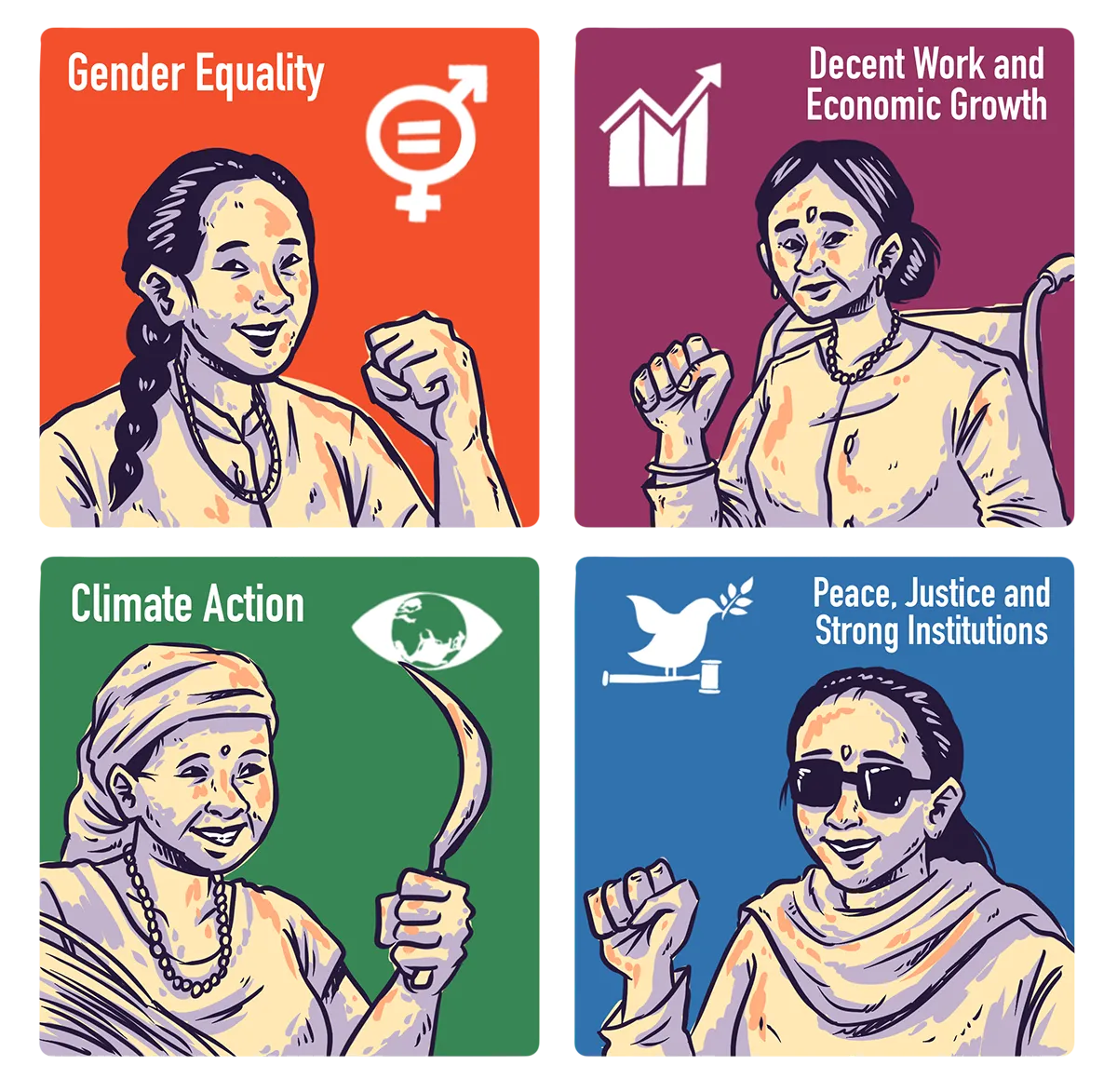

Thematic Concerns for Asia and the Pacific

- Climate Justice

- Financing and Debt

- Decent Work

- Migration

- Women’s Political Participation

- Land, Food and Agriculture

Statistics Database for Asia Pacific

This database of statistics across Asia and the Pacific, sourced from publicly available information was last updated in December 2022.

Please click here for the full database.

About APWLD

Credits

- Writers: Shraddha Chigateri, Asmita Basu, Genevieve Riccoboni

- Illustrators: Jericho Maravilla

- Website design & development: Rodger Firmin

Climate Justice

About

The Asia-Pacific region is more vulnerable to the impacts of climate change than its neighbouring regions. Reasons stem from the region’s geographical location, dependence by large sections of the population on the environment and its natural resources for their livelihood and way of life, widespread poverty and weak institutions.1 The region houses three of the fastest growing economies,2 which ironically, are also three of the largest carbon dioxide emitting countries in the world.3

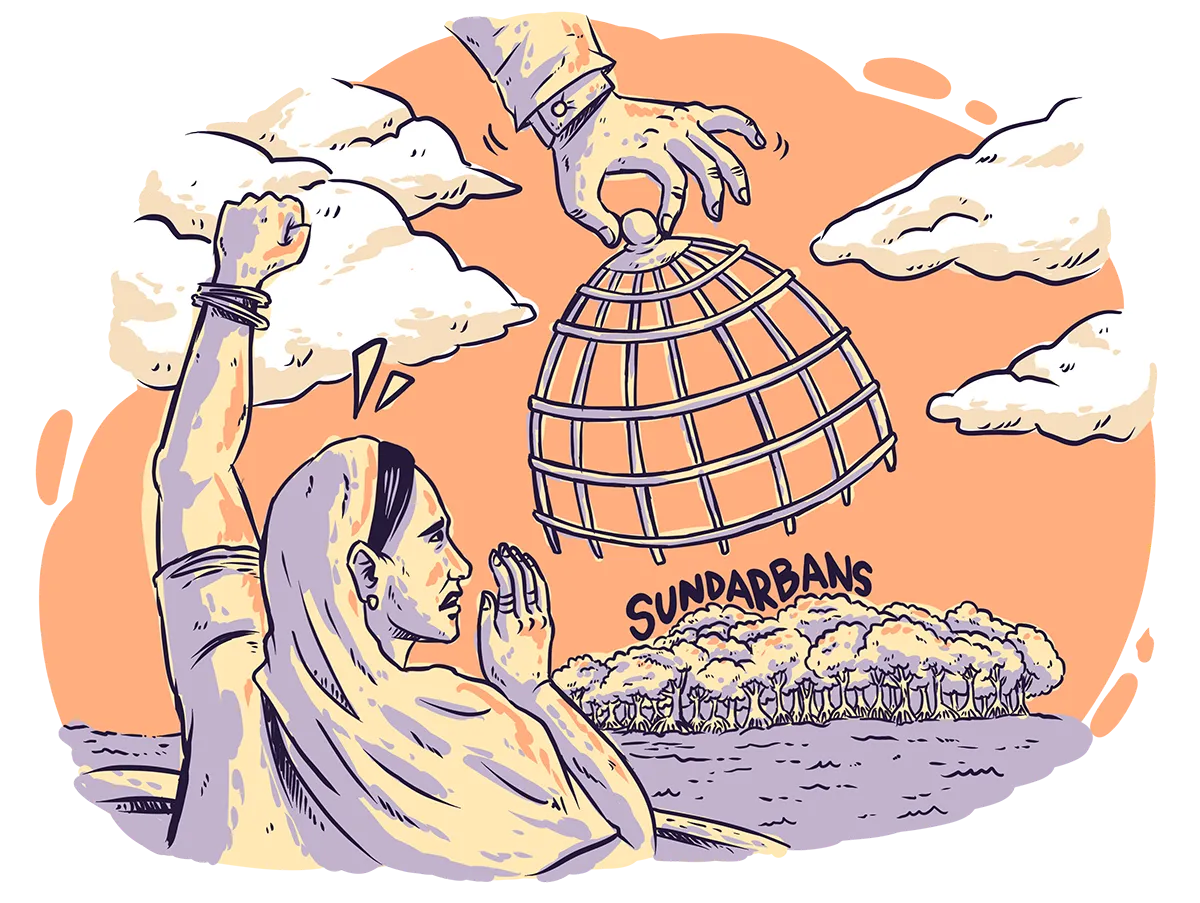

The intensifying impacts of climate change force Asia-Pacific women to the margins as they bear the brunt of natural and human-induced disasters. Extractive trade and investment agreements, corporate capture, land and resource grabbing and patriarchy among others are structural barriers that further surround the climate crisis preventing the achievement of women’s human rights and Development Justice. APWLD and its members work to ensure that climate policies at local, national, regional and international levels incorporate the voices, experiences and demands of Asia-Pacific women’s climate justice movements. It subscribes to and promotes feminist solutions for climate justice and for a Feminist Fossil Fuel Free Future.

Publications

- Financing for Whom? Feminist Analysis on the Global Climate Finance Landscape (2023)

- Undisputed Lived Realities: Feminist Stories in Their Resistance Against Climate Emergencies (Country Briefers) (2022)

- Climate Justice FPAR Country Briefers (2019)

- A Feminist Interpretation of Just and Equitable Transitions in the Context of Climate Change (Briefer) (2018)

- Feminist Fossil Fuel Free Future (5Fs) (2016)

- FPAR Regional Report: Women Warming Up (2015)

- Climate Justice Briefs (2013)

References

- 1 Asian Development Bank Institute. (2012). Highlights. In Anbumozhi, V., Breiling, M., Pathmarajah, S. & Reddy, V. R. (Eds.), Climate Change in Asia and the Pacific: How can countries adapt?. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/159335/adbi-climate-change-asia-and-pacific-how-can-countries-adapt-highlights.pdf

- 2 Ritchie, H., Roser, M. & Rosado, P. (2020). CO2 emissions. Our World In Data. https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions#citation

- 3 Asian Development Bank Institute. (2012). Highlights. In Anbumozhi, V., Breiling, M., Pathmarajah, S. & Reddy, V. R. (Eds.), Climate Change in Asia and the Pacific: How can countries adapt?. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/159335/adbi-climate-change-asia-and-pacific-how-can-countries-adapt-highlights.pdf

- 4 Gautam, V. (2023, June 1). India Emerges As The Fastest Growing Country Among World's Top 5 Economies In First Quarter Of 2023. India Times. https://www.indiatimes.com/worth/news/india-fastest-growing-country-among-worlds-top-5-economies-604528.html

Financing and Debt

About

The Asia-Pacific region suffers from a compounding debt crisis stemming from and continuously reinforced by neoliberal loan conditionalities and debt-servicing impositions. Amidst multiple crises, a number of countries in the region are in debt distress while others have reached default. In order to pay debt, many are forced to adopt austerity measures which ultimately cut down national budgets needed to fulfil basic human rights such as healthcare, education, decent work, adequate housing, food, water and sanitation. Low-income households are forced to shoulder debt acquired in regional and global spaces because of regressive taxation, privatised public services, and inflation among other debt servicing measures.1

APWLD and its members continue to demand for a feminist Financing for Development (FfD), which aligns ongoing financial flows and policies to human rights and development priorities. Principles of FfD also demand the accountability of the Global North and the International Financial Institutions and their mechanisms that have pushed countries in the Asia-Pacific into spiralling amounts of debt, hindering the fulfilment of women’s human rights and Development Justice.

Publications

- Reject IMF-WB! Uphold Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice! (2023)

- Regional Report of the National Monitoring of SDGs and Development Justice 2020-2021 in Asia Pacific (2023)

- We Don’t Owe! We Won’t Pay! Women in Sri Lanka Demand Economic Justice in the Face of the Ongoing Debt Crisis (2023)

- Financing for Whom? Feminist Analysis on the Global Climate Finance Landscape (2023)

- Development Justice Now! Feminist Demands for Financing for Development (Briefer) (2023)

- WTO in a Nutshell: Why Women say No to WTO (Briefer) (2023)

- Briefer on Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) vs Women’s Human Rights in 7 Languages (2022)

- Seven Reasons Why Feminists Say No to World Bank-IMF Neoliberalism (Briefer) (2018)

- RCEP – Robbing Communities to Extract Profit (Briefer) (2016)

- The New Slave in the Kitchen: Debt Bondage and Women Migrant Domestic Workers in Asia (Report) (2012)

References

- 1 APWLD. (2023, October 18). Reject IMF-WB! Uphold Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice!. https://apwld.org/reject-imf-wb-uphold-womens-human-rights-and-development-justice/

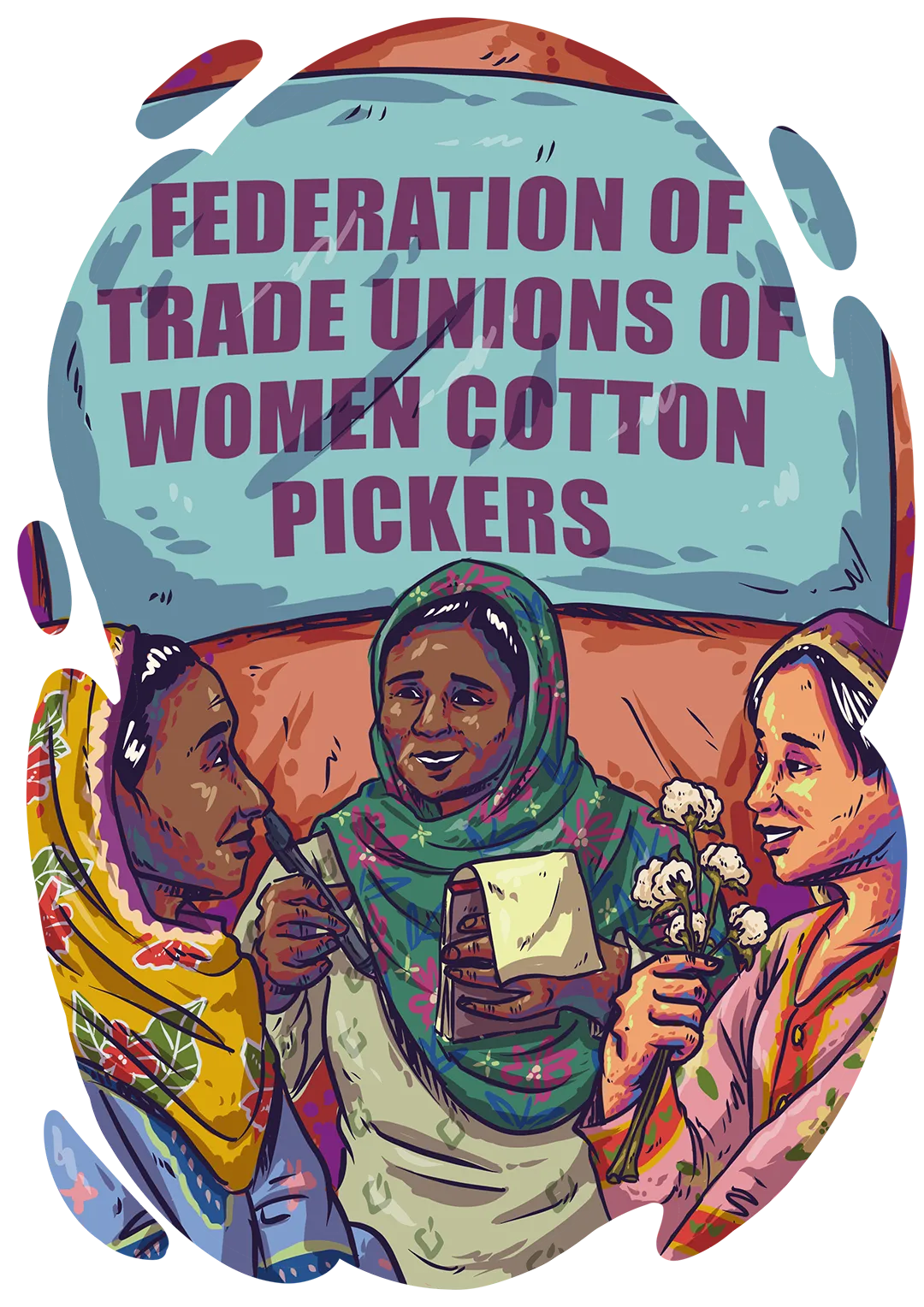

Decent Work

About

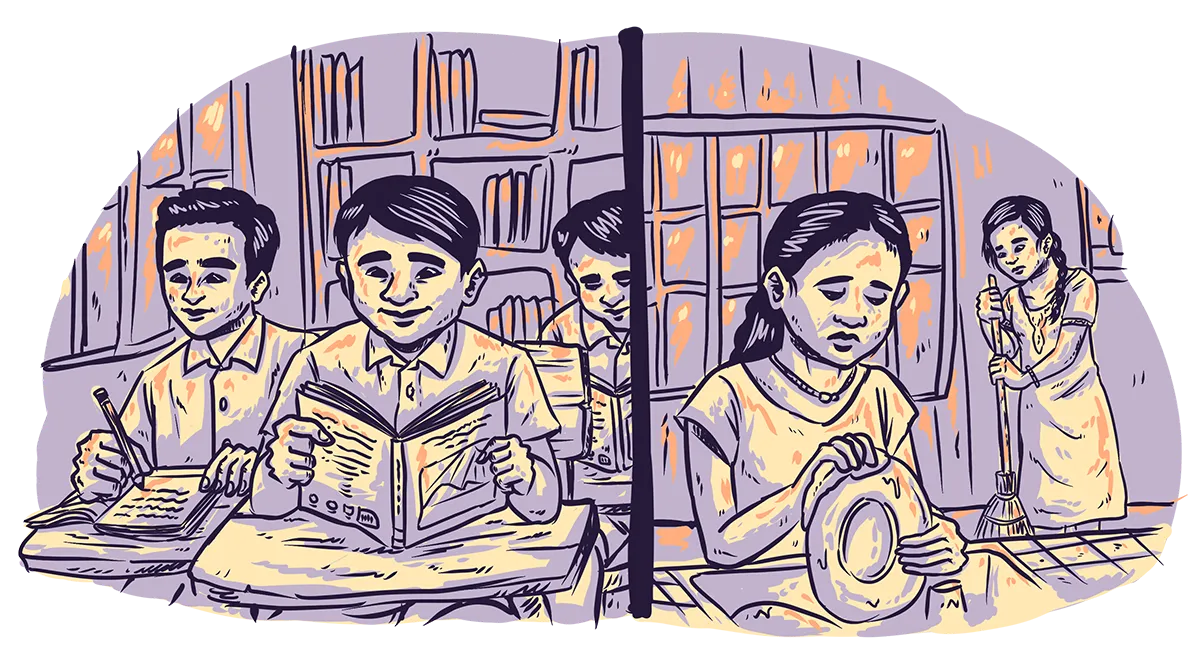

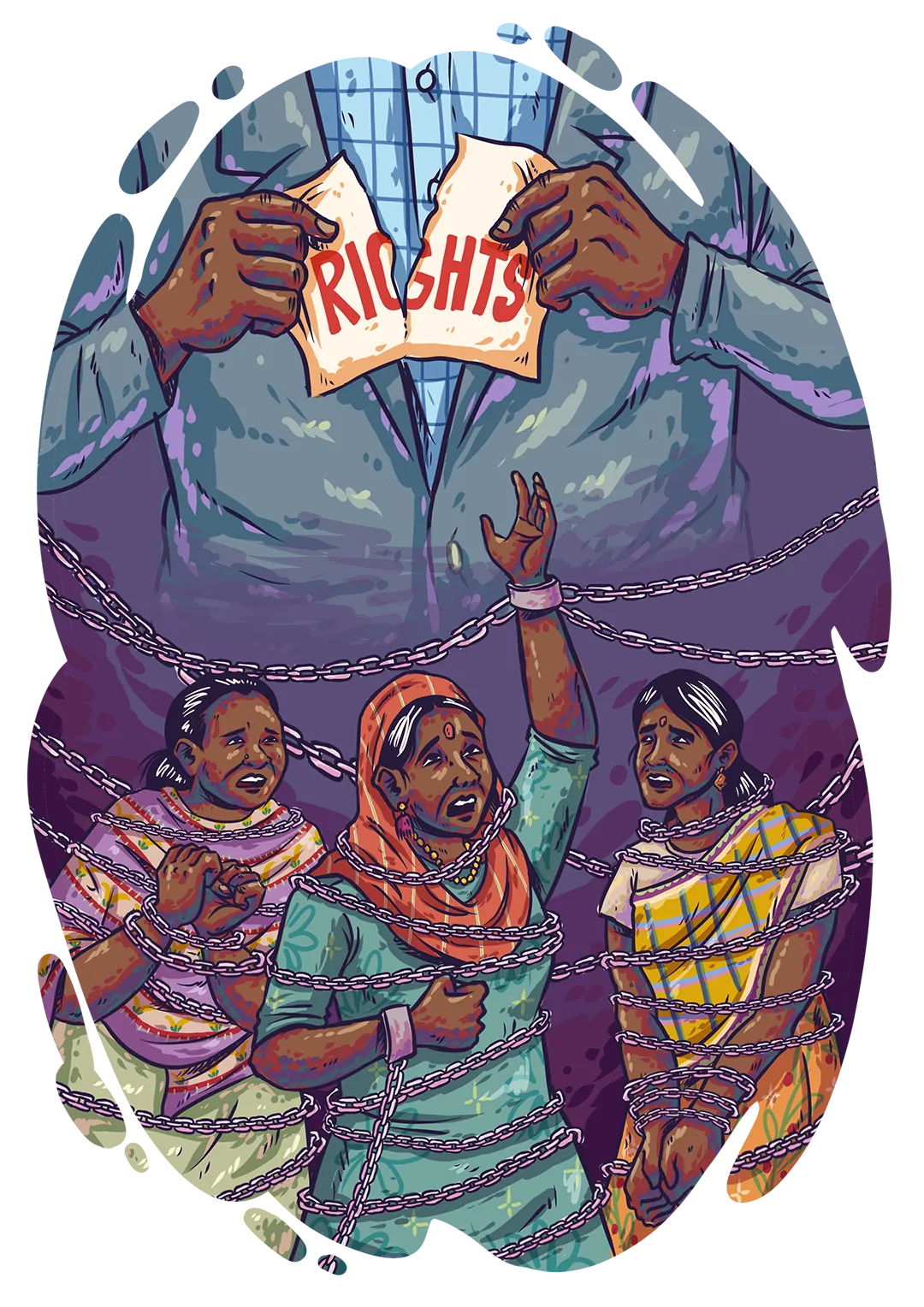

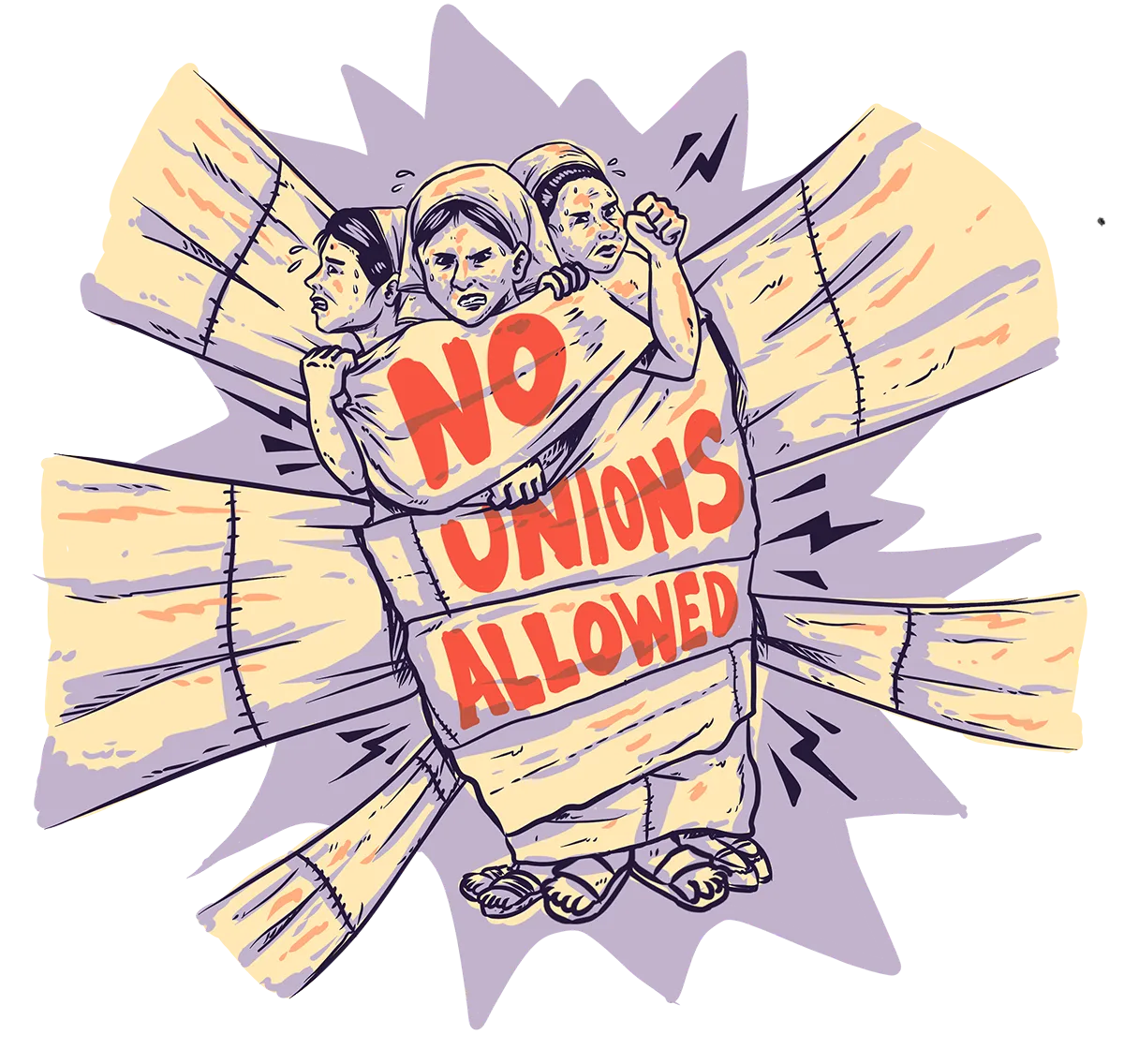

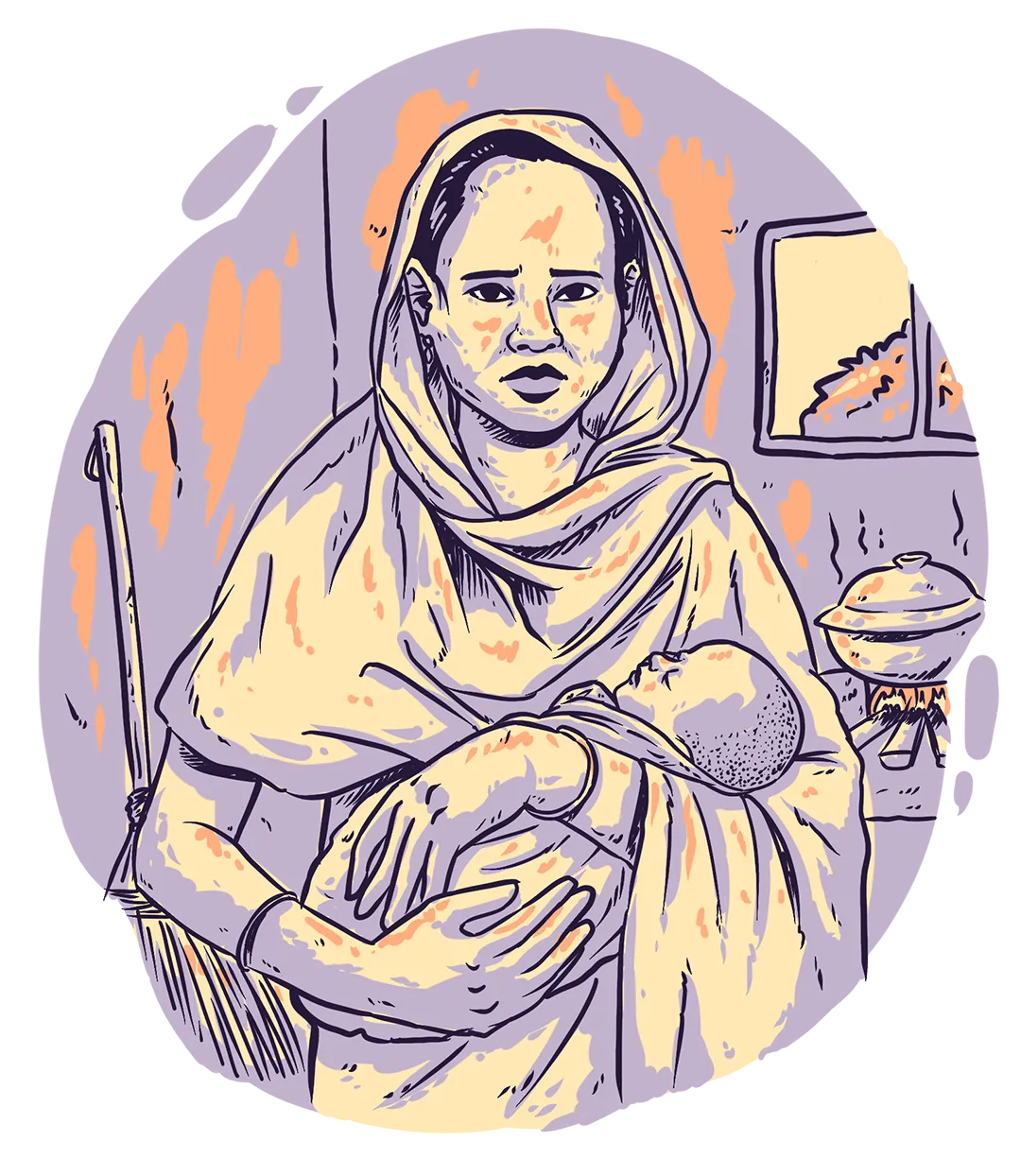

In the Asia-Pacific region, female labour force participation rates are low and have decreased over the years.1 Majority of women employed are often concentrated in precarious, informal, unregulated and low-wage jobs exposing them to labour exploitation, sexual violence and harassment, lack of employment benefits, and unsafe workspaces and conditions. Labour flexibilisation, powered by capitalism and globalisation2 and made legal by oppressive labour laws in the region, increases inequalities. This prevents the fulfilment of women workers’ right to protection, freedom of association and collective bargaining, and decent work.

In addition, Asia-Pacific women are also forced to shoulder the majority of the unpaid care work of the household and the State. Their time spent on paid and unpaid care work is the highest among all the regions in the world.3 APWLD continues to increase capacities, voices and leadership of women workers in the region, build evidence and support networks to foster collective labour rights movements nationally, regionally and globally.4

Publications

- Women Workers in Central Java Special Economic Zones Collectivise to Fight for Their Human and Labour Rights (Country Briefer) (2023)

- Women Garment Workers Demand the Protection of Their Human Rights in the Special Economic Zones of Cambodia (Country Briefer) (2023)

- More questions than answers: Women workers, unions seek actions in recent resolutions posed by ILO Committee of Application of Standards (2023)

- Women Workers Unite to Challenge the Ever-rising Contractualisation and Dehumanisation of Workers in Laguna and Bataan Ecozones, the Philippines (Country Briefer)

- Labour FPAR Country Briefers: BANGLADESH (2023)

- APWLD Oral Statement at the 111th International Labour Conference (2023)

- Fast Track: The US Big Tech Corporations & Women’s Labour Rights (Briefer) (2023)

- Labour FPAR Country Briefers: SRI LANKA (2023)

- Women Sanitation Workers’ Womanifesto for their Labour Rights (2023)

- Global Solidarity Call for Hong Kong Authorities to Release Elizabeth Tang (2023)

- Juddho! Lawan! Confronting Injustices, Marching for Labour Rights (2022)

- Feminist Participatory Action Research Country Brief: Strengthening the Home Based Workers Union to advance women’s labour rights in Hyderabad (2021)

- Feminist Participatory Action Research Country Brief: Organising women street vendors in Phnom Penh to demand labour rights (2021)

- Feminist Participatory Action Research Country Brief: Organising women factory workers in Myanmar to demand their labour rights (2021)

- Feminist Participatory Action Research Country Brief: Organising Domestic Workers in Chennai City for a Living Wage (2021)

- Feminist Participatory Action Research Country Brief: Women Nurses Demand Decent Work in Public Hospitals (2021)

- Feminist Participatory Action Research Country Brief: Organising women cleaners to demand a living wage and improved working conditions in Thai public hospitals (2021)

- Feminist Participatory Action Research Country Brief: Organising women workers at the tea plantation in Assam to demand decent work and a living wage (2021)

- Labour Feminist Participatory Action Research (FPAR) Country Briefs (2019)

- Briefer: What is Living Wage And Why Do We Need It? (2017)

- Decent Work and Living Wage Briefer (2015)

- Know Your Rights Under the New ILO Convention on Domestic Workers (2014)

References

- 1 UNESCAP Social Development Division. (2022). Female Labour Force Participation and the Care Economy in Asia and the Pacific. UNESCAP https://www.unescap.org/kp/2022/female-labour-force-participation-and-care-economy-asia-and-pacific#

- 2 Asmawaty, A. C. (2023, June 13). APWLD Oral Statement at the 111th International Labour Conference. APWLD. https://apwld.org/apwld-oral-statement-at-the-111th-international-labour-conference/

- 3 UNESCAP Social Development Division. (2022). Female Labour Force Participation and the Care Economy in Asia and the Pacific. UNESCAP. https://www.unescap.org/kp/2022/female-labour-force-participation-and-care-economy-asia-and-pacific#

- 4 APWLD. (n.d.). Labour. https://apwld.org/our-programmes/labour/

Migration

About

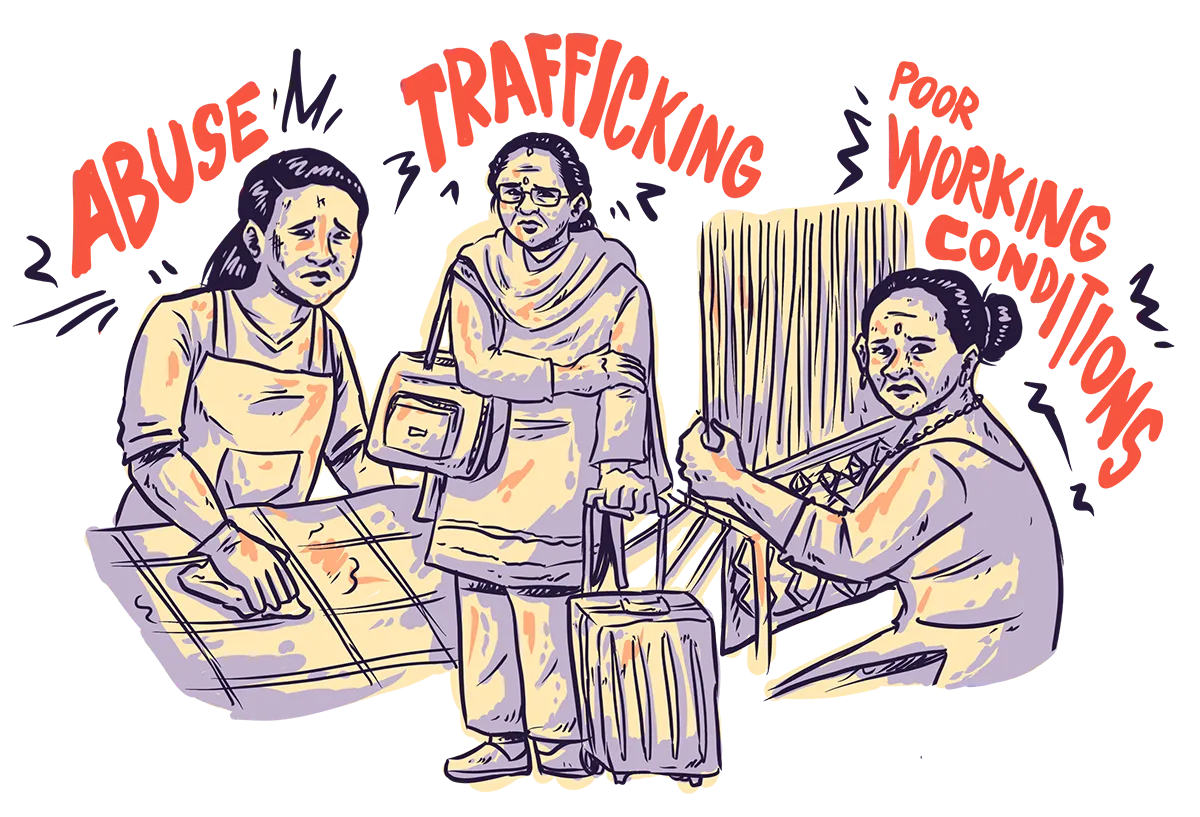

Asia-Pacific countries are simultaneously countries of origin, transit and destination for migrants.1 Reasons for migration include conflict and war, environmental destruction and labour among others. The region is actually the origin of one third of the world’s 169 million migrant workers and ranks as the third subregion hosting migrant workers globally.2 Migration is regarded as a promise of development not just for individuals but also for States. However, this neoliberal model of development puts migrant workers, majority of whom are women, in low wage, low status work which exposes them to discrimination and exploitation with impunity and lack of accountability from origin, transit and destination countries.3

Women migrant workers, whether documented or undocumented, are often deprived of access to justice or remedies, leaving them in a state of debt bondage, as trafficking victims, or in near-death conditions.4 APWLD works with women migrants to build evidence and demand for Development Justice and the fulfilment of their human rights, especially their rights to decent work, protection and freedom of association and civic space.

Publications

- OPEN LETTER: Plea for Release and Return of Mary Jane Veloso (2023)

- Mary Jane Veloso’s Letter to the Presidents of Indonesia and the Philippines (2023)

- From Research to Real Life – A Young Researcher’s Reflection on Cilacap’s Community Exchange Learning and Meeting Mary Jane Veloso (2023)

- Country Briefers on Migration and Decent Work (2022)

- IT’S A JOURNEY WE TRAVEL TOGETHER: Women Migrants Fighting for a Just Society (Regional Report) (2022)

- Recognising and Empowering Migrant Sex Workers as Workers to Gain Legal Protection and Access to Health (Briefer) (2022)

- Protection, Not Restrictions! Organising and Mobilising Returnee Migrant Workers to Lift Gender-Based Migration Bans and Restrictions (Briefer) (2022)

- Empowering Women Migrant Workers Against Sexual And Gender-Based Violence in the Cycle of Migration (Briefer) (2022)

- Organising Indonesian Migrant Domestic Workers in Hong Kong to Combat Overcharging and Illegal Collection of Agency Fees (Briefer) (2022)

- Organising Returnee Migrant Workers Against the Practice of Recruitment Agencies Confiscating Personal Documents (Briefer) (2022)

- Recognising and Protecting the Rights of Internal Migrant Domestic Workers (Briefer) (2022)

- Fighting Behind Closed Doors The Demand for Recognition and the Legal Protection of Domestic Workers in Malaysia (Briefer) (2022)

- Podcast Series: A Glimpse into Two Year Journey of Migration FPAR Partners (2021)

- Stories of Migrant Women (2021)

- Global Compact for Safe, Regular and Orderly Migration (GCM) (Briefer) (2021)

- Dream out of Reach - A Living Wage for Women Migrant Workers in Thailand by MAP Foundation (Briefer) (2018)

References

- 1 Steinmeyer, V. & Graham, S. (2023, August 31). Safe, regular and orderly migration for inclusion and sustainability. UNESCAP. https://www.unescap.org/blog/safe-regular-and-orderly-migration-inclusion-and-sustainability

- 2 International Labour Organization. (2021). ILO Global Estimates on International Migrant Workers – Results and Methodology – Third edition. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---dcomm/---publ/documents/publication/wcms_808935.pdf

- 3 Sheill, K., Lau, K.M., Ambarsari, R. D., Guo, T., Wardarina, Woo, M. & FPAR Partner Authors. (2022). IT’S A JOURNEY WE TRAVEL TOGETHER: Women migrants fighting for a Just Society. APWLD. https://apwld.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/Migration-FPAR-regional-report2019-21.pdf

- 4 APWLD. (n.d.). Migration. https://apwld.org/our-programmes/migration/

Women’s Political Participation

About

Democracies exist in the Asia-Pacific region. Despite this, the region has one of the lowest rates of women’s representation in parliament globally with 21.2 per cent in Asia and 0.6 per cent in the Pacific Islands.1 Where women are able to participate in decision-making processes, their participation is still limited in terms of significant numbers and meaningful opportunities to put forward a feminist agenda. Patriarchy and Fundamentalisms control democratic spaces and contribute to the political disenfranchisement of women in the region, leading to the non-recognition of their issues, needs and agency.

APWLD, with its members and partners, strives towards women’s transformative leadership at all levels of the society that would result in system change, increased democratic participation and the fulfilment of women’s human rights and Development Justice.2

Publications

- Womanifesto: Combating Authoritarianism and Advancing Participatory Democracy (2023)

- Beijing Declaration and Platform for Action (BPfA) and Beijing+25 (Briefer) (2019)

- A Dangerous Unselfishness – Learning from Strike Actions (Briefer) (2019)

- Speak and Be Heard: APWLD Guide to Women’s Tribunals (2016)

References

- 1 UN Women Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific. (2023). Advancing Inclusive Governance in Asia and the Pacific Region (2022-2027). https://asiapacific.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications/2023/03/advancing-inclusive-governance-in-asia-pacific

- 2 APWLD. (n.d.). Women in Power (WiP). https://apwld.org/our-programmes/women-in-power/

Land, Food and Agriculture

About

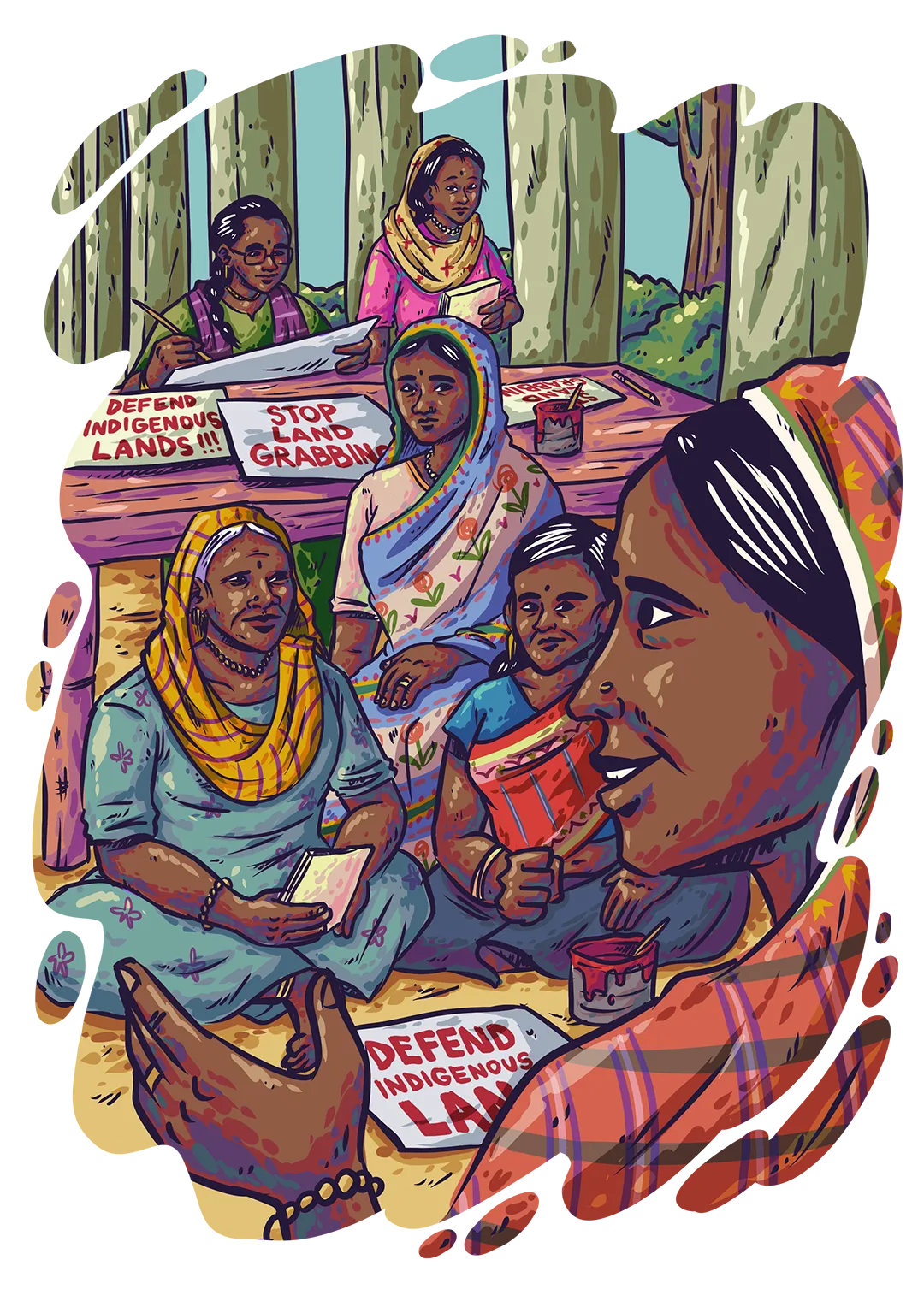

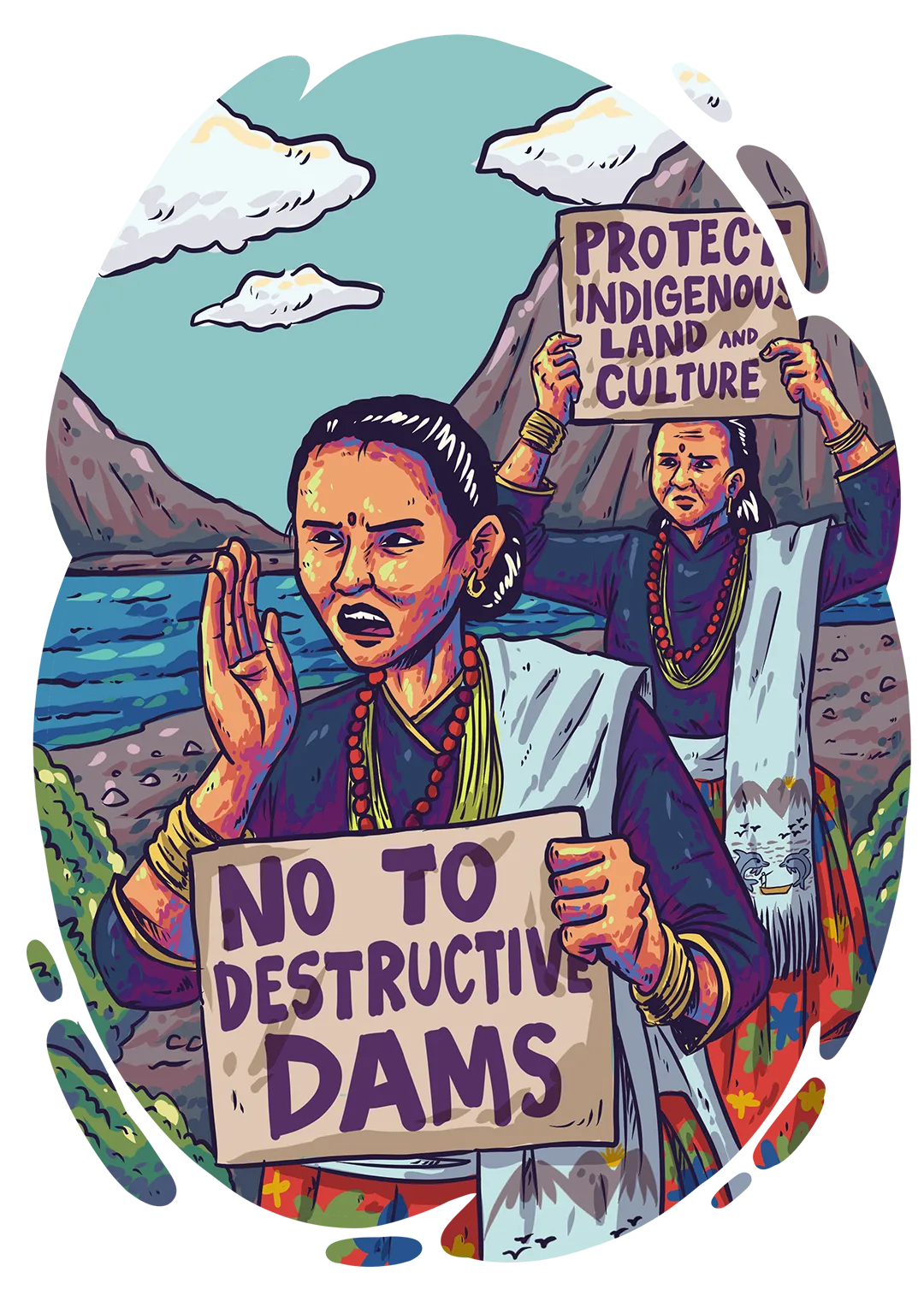

Systemic violations of access to and control over land and natural resources is an issue that impedes the fulfilment of the human rights of Asia-Pacific women and Development Justice in the region. Corporate land and resource-grabbing, conflict over resources and the lack of democratic participation1 erases identities, livelihoods and cultural and food systems, especially that of Indigenous Peoples. The compounding global crises are used as excuses and means to further corporate capture and neoliberal policies, agreements and frameworks that benefit the Global North and the private sector rather than those at the margins.

Women in Asia-Pacific, whose stereotyped roles often tie them to land, food systems and natural resources, are at greater risk of discrimination, violence and poverty. APWLD, with its members and partners, advocates for food sovereignty and the rights to access and control of resources, decent work, peace and democratic participation of women in all their diversities.

Publications

- Unravel Neoliberal Trade: A Failed Solution to Food Sovereignty (Briefer) (2023)

- Women’s Right to Land Through Feminist Participatory Action Research (Country Briefers) (2022)

- Women Interrogating Trade and Corporate Hegemony (WITCH) Country Briefers (2022)

- Stories of Rural, Indigenous, Migrant, Urban Poor Women: Our Struggles, Our Resistance, Our Solidarity! (2022)

- Report on Feminist Perspective on Chin Community’s Customary Laws & Practices (2018)

- Breaking out of Marginalisation - Feminist Participatory Action Research country briefs from 9 countries (2017)

- Feminist Participatory Action Research Regional Report: Our Rights! Our Voices! Our Resources! (2014)

References

- 1 APWLD, Sisterhood Network, NIWF, Unity of Lumad Women, TWU & CVS. (2020, January 15). Expert Mechanism on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Right to Land under the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP): A Human Rights Focus. APWLD. https://apwld.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/APWLD_submission_EMRIP-study_land_2020_15Jan_FINALLL.pdf

About APWLD

APWLD, an independent, non-governmental, non-profit organisation, is the leading network of feminist organisations and individual activists in Asia and the Pacific. With over 268 members from 30 countries and territories in the region, APWLD actively works towards advancing women’s human rights and Development Justice since 1986. It holds a consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council.

Mongolia

Background

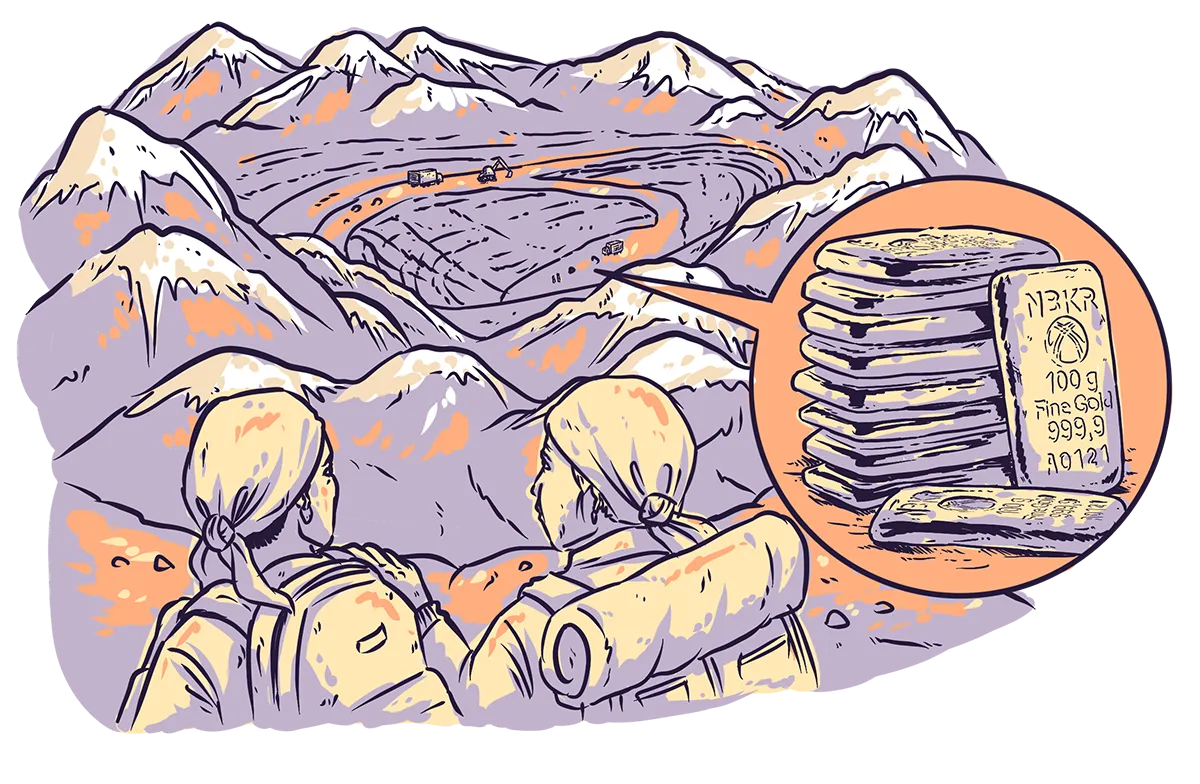

Mongolia1 is a vast landlocked country in East Asia bordered by the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China with a population of approximately 3.3 million people. Demographically, it is one of the youngest countries of the region with a median age of 28.2.2 After decades of the Mongolian political and economic systems being modelled on those of the Soviet Union, the country transitioned from a centrally planned socialist economy to a market economy and from single-party rule to a multi-party democracy in the early 1990s. Since the 2000s, the country’s economy, which has traditionally been based on nomadic pastoralism and agriculture, has become increasingly focused on extractive industries targeted at the country’s extensive deposits of copper, gold, coal and other minerals.

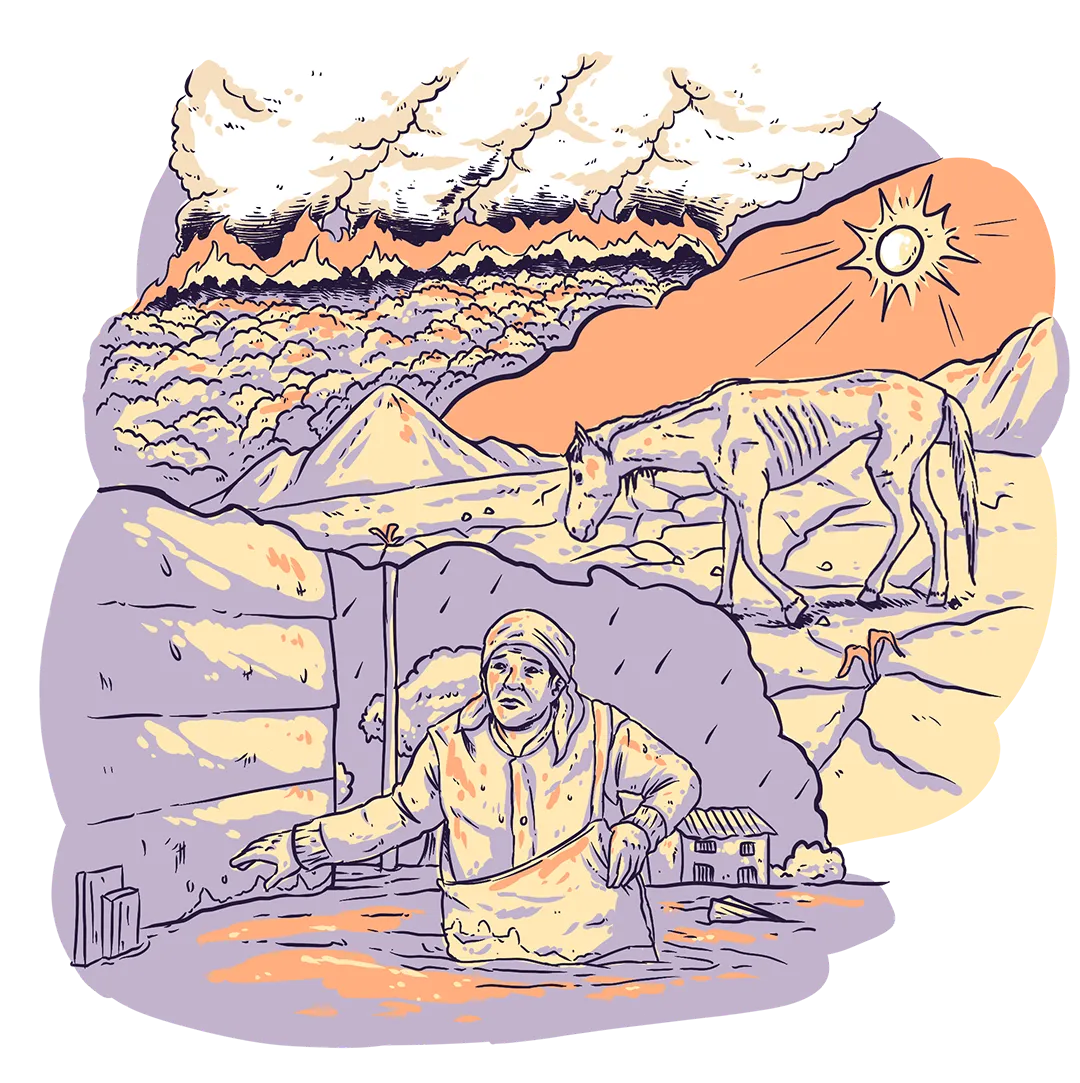

Bolstered by foreign investment, the extractive industry has grown rapidly since 2000, and in 2021, it accounted for 24 per cent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), 67 per cent of its industrial sector and 93 per cent of exports.3 Despite the size of investment in the sector, there has not been a substantive increase in the number of jobs in the sector. Moreover, given that the sector requires the use of large tracts of land, it has had deep impacts on women’s human rights and Development Justice by detrimentally impacting the lives and livelihoods of women, especially those that are rooted in Mongolia’s pastoral economy. The mining sector has also contributed to the increased susceptibility of the country to adverse climate change.

Over the years, there has also been a significant urbanisation of the country with employment and educational opportunities being concentrated in the capital city, Ulaanbaatar, which houses 1,672,627 people constituting over half of Mongolia’s total population.4 Despite significant shifts in the political and economic context of Mongolia, rising inequalities and high levels of poverty and unemployment pose serious challenges for Development Justice in the country. According to the 2020 Household Socio-Economic Survey (HSES), the national official poverty rate in 2020 was 27.8 per cent, barely 0.6 percentage points lower than in 2018, with the pandemic stalling poverty reduction efforts.5 While the sharp increase in rates of unemployment during the pandemic have since abated, labour force participation rates continue to remain at pre-pandemic levels as do large gender gaps in labour force participation.6 Similarly, in terms of gendered inequalities, the country’s Gender Inequality Index is below the regional and global average, pointing to several systemic barriers in the achievement of women’s human rights and Development Justice in the country.

View Case Stories / Map

View Country Statistics

International Treaties/Conventions

Systemic Barriers in Achieving Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice

- Finance, Trade, and Investment Agreements

Since it transitioned to a market economy in the early 1990s...

- Corporate Capture

Over recent years, state policies in Mongolia have been largely supportive of large...

- Land and Resource Grabbing

Given the enduring history of centuries of Mongolian...

- Climate Crises

Mongolia has seen an intensifying series of climate crises in the form of substantially...

- Militarism and Conflict

Unlike other countries of the region, military spending in Mongolia has seen...

- Patriarchal Authoritarian Governance

In its latest assessment of civic space in Mongolia, CIVICUS found...

- Patriarchal Structures and Norms

Through the difficult transition years when many families were...

Accountability

Sustainable Development: Structures of AccountabilityIn 2016, Mongolia signed and ratified the 2030 Agenda for...

Accountability

Women's Rights Groups Demand AccountabilityBased on the specific challenges and problems faced by women and communities in Mongolia, women’s rights’ organisations...

Recommendations

Women’s Priority Issues and RecommendationsGeneral Recommendations | end poverty, promote decent work | achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls | ensure strong institutions | tackling the adverse impacts of the mining sector

References

- 1 This country profile is primarily based on the 2019 Peoples’ Development Justice report entitled ‘Sustainable Development and our Participation’ by MONFEMNET National Network and Centre for Human Rights and Development (CHRD), Mongolia prepared under the aegis of APWLD’s ‘Women 2030: Monitoring and Evaluation of Sustainable Development Goals and Development Justice’ project. Any additional references, including updated citations, are separately cited.

- 2 Worldometer. (2023, July 16). Mongolia Population (Live). https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/mongolia-population/

- 3 Mongolia EITI National Secretariat. (2022, December). Mongolia 2021 EITI Report: Report on Mongolia’s Extractive Sector. https://eiti.org/documents/mongolia-2021-eiti-report

- 4 World Population Review 2023. (n.d.). Ulaanbataar Population 2023. https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/ulaanbaatar-population

- 5 World Bank. (2021, 30 December). Mongolia’s 2020 Poverty Rate Estimated at 27.8 Percent. https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/press-release/2021/12/30/mongolia-s-2020-poverty-rate-estimated-at-27-8-percent

- 6 World Bank. (2023, 21 April). Mongolia Economic Update - Partial Recovery and Lingering Risks (English). https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/099413204212338504/idu0c9bb5b690643104ccf091520b7f0565236e4

China

Background

The Peoples’ Republic of China1 is the fourth largest country in the world by area, bordered by 14 countries, and sharing a maritime border with a further seven countries. It is the world’s largest economy by Purchasing Power Parity (PPP), with 33 trillion USD in 2023.2 It is also the world’s largest manufacturing economy and exporter of goods. Additionally, until recently, it was also the world’s most populous country in the world with over 1.45 billion people in 2023.3 Since 1978, when China shifted from a state-led communist economic system by initiating its ‘Opening and Reform’ policy, it has been one of the fastest growing economies of the world. Identifying its economy as ‘socialism with Chinese characteristics’, it has striven to achieve economic growth through the introduction of foreign capital and technology while purportedly maintaining its commitment to socialism.4

Bolstered by foreign investment, the extractive industry has grown rapidly since 2000, and in 2021, it accOne of the ways in which China has demonstrated its focus on the most marginalised has been through its prioritisation of poverty eradication. From 2017 to 2020, the central government has invested heavily and increased its budget for poverty eradication from 13.1 billion USD in 2017 to 22.3 billion USD in 2020. In 2021, in its Voluntary National Review (VNR) report, China declared that it had eradicated extreme poverty 10 years ahead of schedule, lifting 55.7 million rural residents out of poverty over a five-year period from 2015-2020.5

Even so, the economic growth story of China is also a story of worsening inequalities. Since 1978, the share of income of the top one per cent has steadily increased, just as the share of income of the bottom 50 per cent has steadily decreased. In 1978, the top one per cent earned 6.5 per cent of total income, whereas they earned 15.6 per cent in 2020.6 On the other hand, the bottom 50 per cent earned 25.2 per cent of total income in 1978, which had decreased drastically to 13.7 per cent in 2020. Similarly, in terms of wealth inequality too, in 1995, the top one per cent and the bottom 50 per cent had a net personal wealth nearly equivalent to each other at 15.8 and 16 per cent respectively. Since then, there has been a steep and stark growth in inequalities with the top one per cent capturing four times the wealth of the bottom 50 per cent in 2021 at 32.6 per cent and 6.2 per cent respectively.7 In terms of Ultra High Net Worth Individuals, although the number of billionaires decreased from 698 in 2021 to 562 in 2023 owing to the pandemic and geopolitical tensions, China continues to have the second largest number of billionaires in the world after the United States (US).8

Apart from deepening inequalities, Chinese society faces many other social challenges including an aging population, deteriorating environment, regional inequalities, gendered inequalities, human rights issues, other issues arising from urbanisation and so on. In 2021, China ranked 79 out of 191 countries and territories on the Human Development Index.9

View Case Stories / Map

View Country Statistics

International Treaties/Conventions

Systemic Barriers in Achieving Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice

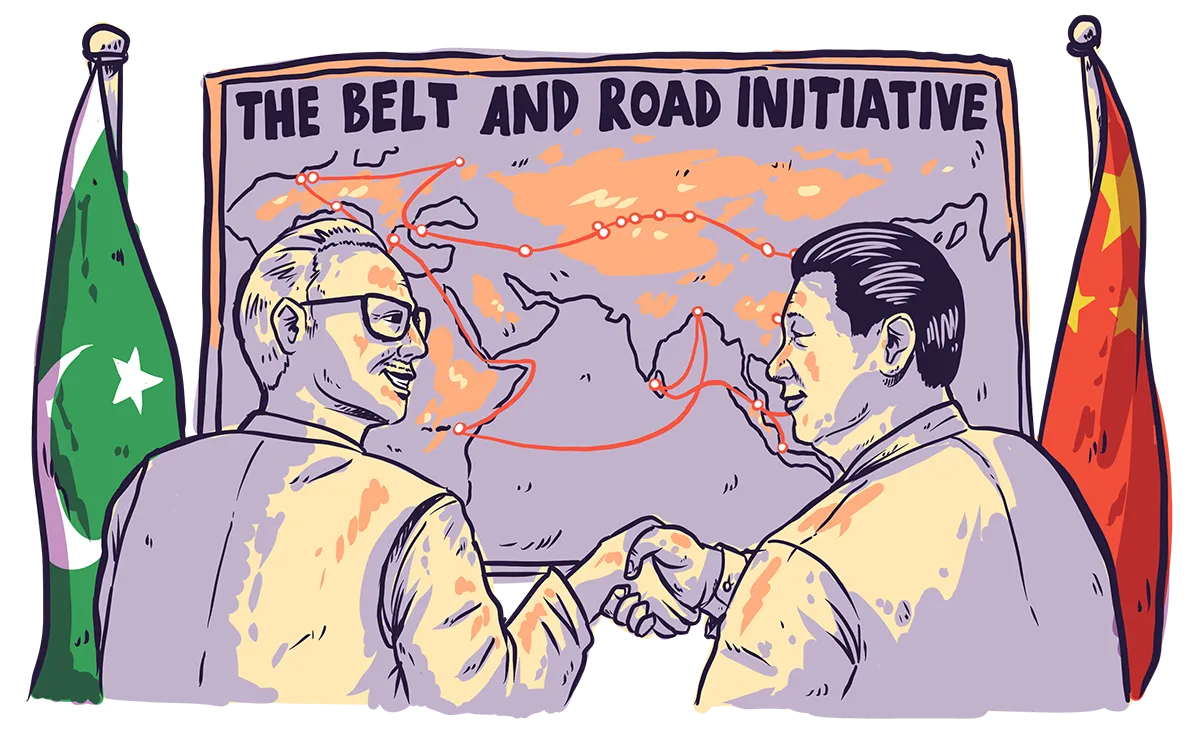

- Finance, Trade, and Investment Agreements

Since initiating its ‘Opening and Reform’ policy in the late 1970s...

- Corporate Capture

The number and size of Chinese companies are increasing vastly. In 2020...

- Land and Resource Grabbing

In China, the state claims ownership of all land and natural resources...

- Climate Crises

The shift of global manufacturing to China has made the country more vulnerable...

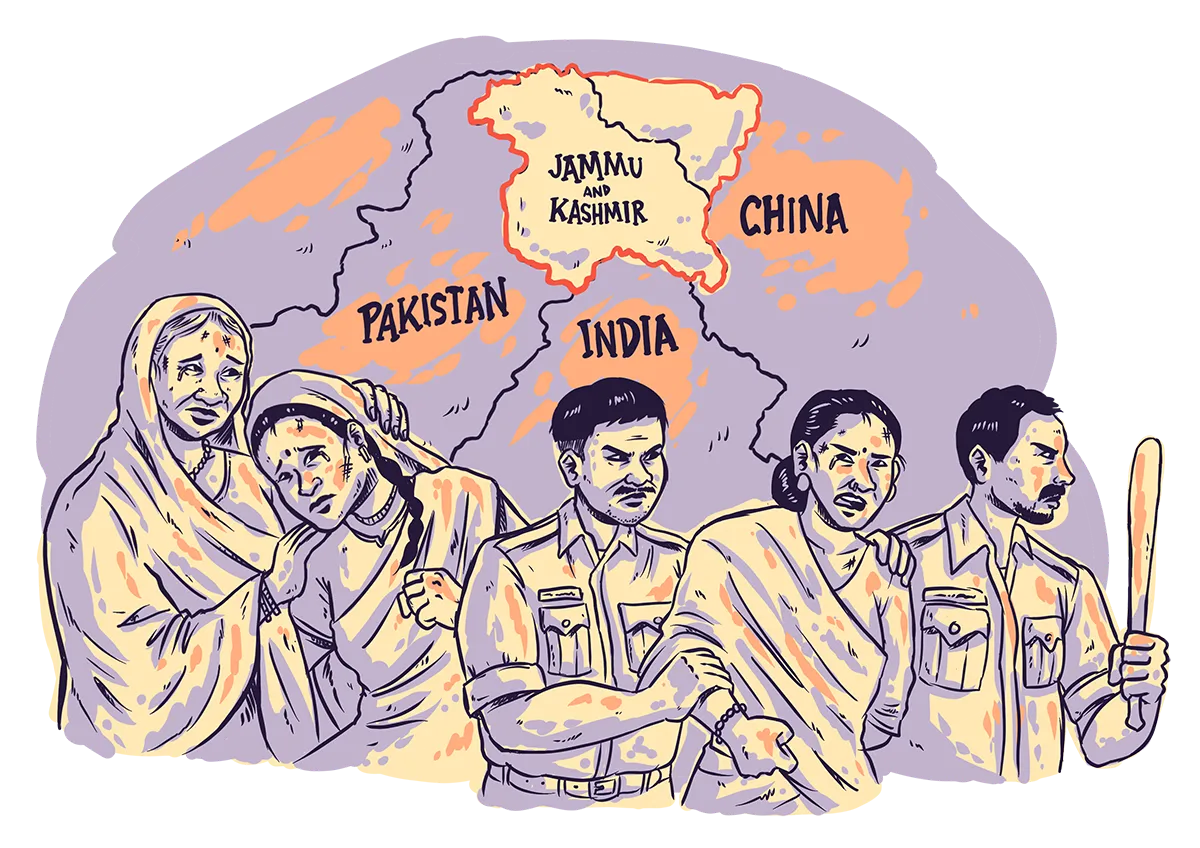

- Militarism and Conflict

China is a highly militarised country, and its defence spending has been growing...

- Patriarchal Authoritarian Governance

Since his ascendancy to the Chinese Presidency, President......

- Patriarchy and Fundamentalism

China has a long history of recognising formal equality...

Accountability

Sustainable Development: Structures of AccountabilityIn October 2016, a few months after the 2030 Sustainable Development...

Accountability

Women's Rights Groups Demand AccountabilityBased on the specific challenges and problems faced by women and LGBTQIA+ communities...

Recommendations

Women’s Priority Issues and RecommendationsGeneral Recommendations | addressing Gender-Based Violence | COVID-19 recovery strategy

References

- 1 This country summary draws primarily on the Peoples’ Development Justice Report prepared by Beijing-SDG 5 Facilitating Group in partnership with APWLD in 2021 entitled, ‘China: Women Demand Stronger Political Will and Real Actions to Stop Gender-Based Violence’. Any additional references, including updated citations, are separately cited.

- 2 International Monetary Fund. (2023). GDP, current prices. https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/PPPGDP@WEO/OEMDC/ADVEC/WEOWORLD/CHN

- 3 The population of China has just recently been surpassed by India.

- 4 Kobayashi, S., Baobo, J. & Sano, J. (1999). The "Three Reforms" in China: Progress and Outlook. Japan Research Institute. https://www.jri.co.jp/english/periodical/rim/1999/RIMe199904threereforms/

- 5 Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China. (2021). China's VNR Report on Implementation of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. United Nations. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/280812021_VNR_Report_China_English.pdf

- 6 World Inequality Database. (n.d.). Income Inequality, China, 1978-2019. https://wid.world/country/china/

- 7 World Inequality Database. (n.d.). Income Inequality, China, 1978-2019. https://wid.world/country/china/

- 8 Flannery, R. (2023, April 4). The 10 Richest Chinese Billionaires 2023. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/russellflannery/2023/04/04/the-10-richest-chinese-billionaires-2023/?sh=79a0958b5ddd

- 9 United Nations Development Programme. (2022, September 8). Human Development Report: China (2021). https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/specific-country-data#/countries/CHN

Vanuatu

Background

Vanuatu1 is an archipelago consisting of over 80 islands, home to approximately 300,000 people, with the majority residing in rural areas and engaged in subsistence farming. The nation gained independence from France and Britain in 1980 and has largely been shielded from the civil and political unrest seen in nearby Melanesian countries. Despite consistently ranking among the world’s happiest nations, it holds the 140th position out of 191 countries on the Human Development Index (HDI).2 Relying mainly on agriculture and tourism, its economy struggles to cater to its growing, youthful population, limiting employment options. Vanuatu ranks foremost among the nations most susceptible to climate change, enduring regular cyclones, with the latest (at the time of this report) in March 2023. Climatic challenges, compounded by the COVID-19 pandemic, have hindered economic growth, costing roughly six per cent of its GDP annually. The country’s health and education sectors are inadequately equipped for the expanding population, with women and girls particularly affected by limited access to family planning and quality education. Increased foreign investment, especially in areas like Port Vila, has led to acquisitions of communal land and subsequent displacement of indigenous families. Dominant patriarchal norms and deep-rooted cultural practices undermine women’s societal position, manifesting in widespread Violence Against Women (VAW). Traditional responses to such violence often fall short in providing justice or redress for women.

View Case Stories / Map

View Country Statistics

International Treaties/Conventions

Systemic Barriers in Achieving Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice

- Finance, Trade and Investment Agreements

Vanuatu became a member of the World Trade Organisation...

- Poverty

Although the levels of the consumption-based poverty...

- Land and resource grabbing

In Vanuatu, freehold land is non-existent. All urban territories...

- Militarism and Conflict

Vanuatu lacks formal military forces. Instead, its security apparatus...

- Patriarchy

Vanuatu’s Constitution, established in 1980, guarantees the0...

- Women in leadership roles

Traditional beliefs and customs uphold male dominance and customary...

- Women and education

In the 2020 Census, women represented 48.7 per cent of those...

- Women and employment

In the 2020 census,the Labour Force Participation Rate (LFPR) for...

- Women and health

In 2023, life expectancy in Vanuatu was 73 for women and 68 for men...

- Violence against women

Violence against women is a significant concern in Vanuatu. The 2011...

- Patriarchal Authoritarianism

The Constitution provides for rights to freedom of expression...

- Climate Crisis

Vanuatu, despite being a carbon negative nation, bears the unfortunate...

Accountability

Women’s Rights Groups Demand AccountabilityVanuatu's framework for monitoring the Sustainable Development Goals...

Recommendations

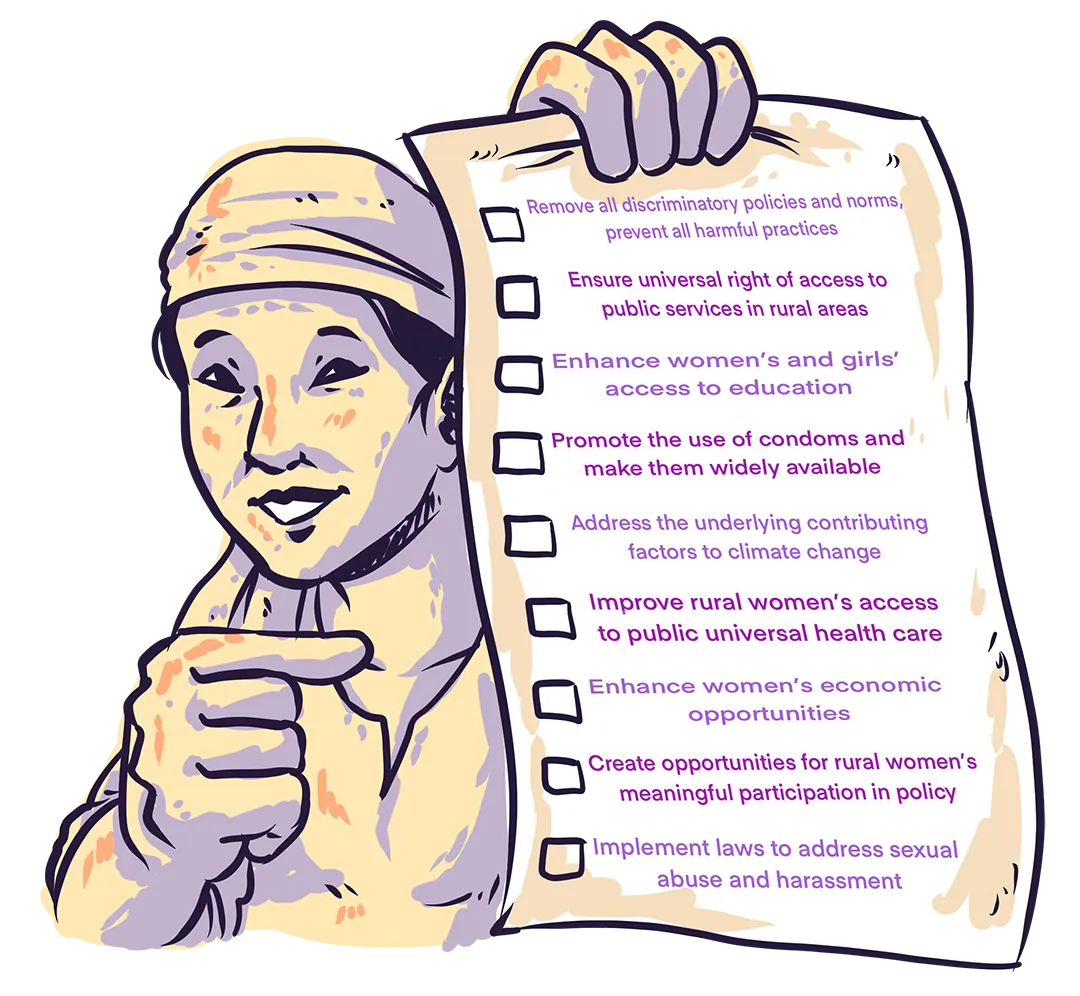

Women’s Priority Issues and RecommendationsIn 2017, Vanuatu Young Women for Change (VYWC) conducted

References

- 1 This country profile is based on the 2018, ‘2030 Monitoring and Review of Sustainable Development Goals and Development Justice by Vanuatu Young Women for Change (VYWC)’, Vanuatu prepared under the aegis of APWLD’s ‘Women 2030: Monitoring and Evaluation of Sustainable Development Goals and Development Justice’ project. Any additional references, including updated citations, are separately cited.

- 2 The HDI is a summary measure for assessing long-term progress in three basic dimensions of human development: a long and healthy life, access to knowledge and a decent standard of living. UNDP. (2022, September 8). Human Development Index: Vanuatu. https://hdr.undp.org/data-center/specific-country-data#/countries/VUT

Fiji

Background

Fiji1 is an archipelagic nation comprising 332 islands and home to a population of approximately 925,000 people. Fiji has made significant strides towards promoting development and advancing the status of women, but progressive legislative reforms are far outweighed by existing and entrenched barriers to truly achieving women’s human rights and Development Justice.

Strong patriarchal practices dominate decision-making structures with little to no participation of women. Women’s share of formal employment is significantly lower than men’s, and women remain relegated to the low-wage end of the labour market. Rural women face significant barriers to accessing, controlling and owning land as traditional institutions allow them limited rights to inherit land, own property, or access financial and legal services to purchase land.

Corporate capture of land and resources continue to harm the environment and threaten the livelihoods of local people. Gender equality and sustainable development are also impeded by the climate crisis, as it is women who bear the greatest burden of the impacts of climate change.1 Further, Fiji’s tumultuous political situation in recent decades has left a legacy of militarism that continues to stifle the participation of civil society in decision-making processes.

View Case Stories / Map

View Country Statistics

International Treaties/Conventions

Systemic Barriers in Achieving Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice

- Finance, Trade and Investment Agreements

The Fijian economy is predominantly made up of services (70%)...

- Corporate Capture

The issue of corporate capture must be contextualised within the ...

- Land and Resource Grabbing

In Fiji, land is managed under three distinct systems: Native Land...

- Militarism and Conflict

Since gaining independence in 1970, Fiji has faced significant...

- Patriarchy

Fijian culture is fundamentally rooted in patriarchal systems, characterised...

- Patriarchal Authoritarian Governance

The 2013 Constitution guarantees rights to freedom of expression...

- Climate Crises

Fiji, a small island state, is acutely exposed to the ravages of climate...

Accountability

Sustainable Development: Structures of AccountabilityAs evident from Fiji’s 2023 Voluntary National Review (VNR), Fiji's commitment to the 2030 Agenda faces substantial challenges, notably in the domains of Sustainable...

Recommendations

Women’s Priority Issues and RecommendationsThe lack of women’s participation in the SDG’s monitoring process was identified

References

- 1 This country profile is primarily based on the 2019 Peoples’ Development Justice report entitled ‘Working for Gender Inclusive Peace and Development for Fiji’ by Fiji Women’s Forum, prepared under the aegis of APWLD’s ‘Women 2030: Monitoring and Evaluation of Sustainable Development Goals and Development Justice’ project. Any additional references, including updated citations, are separately cited.

Philippines

Background

The Philippines is an archipelagic nation located in Southeast Asia in the western Pacific Ocean with a population of over 118 million people. It consists of over 7,000 islands, and is incredibly rich in biodiversity, natural resources such as minerals, fertile agricultural lands, and extensive coastlines and marine life. The Philippines shares maritime borders with Taiwan, Japan, Palau, Indonesia, Malaysia, Vietnam, and China. It is 54 per cent urban, and the Manila metropolitan area is the most densely populated city in the world, home to over 14 million people.1 Historically, the lands which comprise the modern-day Philippines were home to diverse groups and sultanates among others that were influenced by cultures across Asia, and at times were part of larger empires. Approximately 12 to 15 per cent of the contemporary Philippine population is considered to be Indigenous Peoples.2 The Philippines is heavily vulnerable to typhoons, earthquakes, floods, landslides, tsunamis, and volcanic eruptions, making it one of the top ten most disaster-prone countries in the world. According to the Global Climate Risk Index, it was the fourth most affected by climate change between 2010-2019.3

Spain colonised the Philippines, uniting it into a single political structure, for 333 years.4 After this period, it came under the control of the United States as a territory until World War II. During the war it was also occupied by Japan, during which period there were war crimes including sexual violence and slavery systematically perpetrated against women.5 The post-independence period has been marked by successive political transitions including the dictatorship of Ferdinand Marcos, Sr., who ushered in a period of intense violence, repression, and exploitation of resources in Indigenous lands. For over 50 years since the dictatorship era, successive governments have waged an armed conflict with communist insurgent groups throughout the country, occupying the lands of Indigenous Peoples with devastating impacts on rural communities, and have also fought against Muslim separatist movements particularly in Mindanao.6 Throughout its modern history, the Philippines has maintained a very close military, trade, and political relationship with the United States, which has positioned it geopolitically within great power struggles.

The country faces many barriers to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and to Development Justice, many of which are rooted in the prevailing neoliberal development model that centres market competition and free trade. In the past few decades, the economy has transitioned more away from agriculture and manufacturing and towards the service sector, which now comprises 60 per cent of the country’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP).7 Rising sectors such as the Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) sector, which now has over one million people employed in it, are part of this economic transition.8 Government policies and programmes have increasingly given local and foreign corporations the opportunity to grab productive resources to make profits, with the advantage of tax cuts and priority treatment to operate in Special Economic Zones (SEZs). In addition, remittances from Filipinos working overseas are almost 10 per cent of the country’s GDP now.9 Despite these developments and the immense natural resources in the country, wealth is not distributed equitably: approximately a quarter of the population is living below the national poverty line, and the country overall has a medium level of human development on the Human Development Index (HDI). Where traditional sectors like agriculture do remain, the sector is heavily marked as well by foreign investment in large agribusiness that displaces smaller farmers and Indigenous Peoples. All of these development strategies have had direct impacts on the lives of women and girls, including through promoting low wage employment, displacement, and diversion of investments away from social services.

View Case Stories / Map

View Country Statistics

International Treaties/Conventions

Systemic Barriers in Achieving Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice

- Finance, Trade, and Investment Agreements

During the 1990s, the Philippines made significant strides to open...

- Influence of Private Capital

Since the 1980s, privatisation has gained momentum...

- Land and Resource Grabbing

As with many other formerly colonised countries, patterns of...

- Climate Crises

Located in the cyclone belt and the Pacific Ring of Fire...

- Militarism and Armed Conflict

Extreme militaristic culture, rooted in patterns of colonialism...

- Patriarchal Authoritarian Governance

Civil Society Organisations (CSOs) in the Philippines experience...

- Patriarchal Structures and Norms

Patriarchal values continue to reinforce women’s lack of...

Accountability

Sustainable Development: Structures of AccountabilityThe government of the Philippines has committed to achieve the...

Recommendations

Women’s Priority Issues & RecommendationsQuality Education | Decent Work | Reduced Inequalities....

References

- 1 World Population Review. (2024). Manila’s Population Growth. https://worldpopulationreview.com/world-cities/manila-population

- 2 APWLD. (n.d.). Lumad women defending their indigenous right to ancestral land and resources in Mindanao. https://apwld.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Philippines-Land-FPAR-Sabokahan.pdf

- 3 Eckstein, D., Künzel, V., & Schäfer, L. (2021). Global Climate Risk Index 2021. Germanwatch. https://www.germanwatch.org/en/19777

- 4 Philippine Consulate of Armenia. (n.d.). About the Philippines. https://philippineconsulate.am/about-the-philippines/

- 5 University of Hawaii at Manoa Library. (n.d.). Philippines. https://guides.library.manoa.hawaii.edu/c.php?g=105238&p=687104

- 6 APWLD. (n.d.) Lumad women defending their indigenous right to ancestral land and resources in Mindanao. https://apwld.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/Philippines-Land-FPAR-Sabokahan.pdf

- 7 Investopedia. (2015, September 09). Emerging Markets: Analyzing the Philippines’ GDP. https://www.investopedia.com/articles/investing/091815/emerging-markets-analyzing-philippines-gdp.asp

- 8 Arenas, G. & Coulibaly, S. (Eds.) (2022). International Development in Focus: A New Dawn for Global Value Chain Participation in the Philippines. World Bank Publications. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/73ea3565-605f-59ed-a982-c20b12b50524/content

- 9 Agcaoili, L. (2023, February 16). Remittances hit record high $36.1 billion in 2022. Philstar.com. https://www.philstar.com/business/2023/02/16/2245201/remittances-hit-record-high-361-billion-2022

Indonesia

Background

Indonesia is a vast archipelagic nation of over 17,000 islands that is located in Southeast Asia and Oceania. It is the biggest economy in Southeast Asia; the world’s fourth most populous country with over 278 million people; and is the world’s most populous Muslim majority country. The population of Indonesia is ethnically and linguistically diverse, with approximately 300 distinct ethnic groups and more than 700 spoken languages. Historically, the lands which are now part of Indonesia were the home to different states, many of which were connected to the world through trade, particularly in spices.

Starting in the early 17th century, the Dutch East India company began colonising these lands and established control over much of modern-day Indonesia. The Dutch republic later took over from the Company, and persistently waged war against Indigenous leaders who resisted their rule and attempted to gain control of further territory. Colonisation forcibly established monopolies over trade, introduced and imposed the cultivation of non-native cash crops, expanded slavery, exploited fossil fuel resources including coal and oil, and militarised lands through the buildup of military fortresses. Indonesia became an independent state in 1945 in the wake of the Second World War. Today, it borders Malaysia, Papua New Guinea, and Timor-Leste, and shares maritime borders with Singapore, Vietnam, Thailand, Philippines, Australia, Palau, and India.

Although it is heavily urbanised, and Jakarta is the second most populous urban area in the world, Indonesia also has immense biodiversity of flora and fauna. Ecologically, Indonesia is located within the Pacific Ring of Fire and experiences high volcanic and earthquake activity. Over the past decades, this biodiversity and the environment has been threatened by widespread deforestation, including for the purposes of palm oil cultivation. In 1950, forests covered 87 per cent of the land area,1 but by 2020, the forest cover was only 49 per cent. There has also been extensive exploitation of marine resources, increased air pollution from the intensification of industrial and agricultural activity, and destruction of peatland. This environmental exploitation, which mirrors and expands on the patterns established during the colonial periods, has both damaged the ecology of Indonesia as well as been detrimental to Indigenous Peoples’ rights and labour rights.

Indonesia faces many barriers to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), including natural disasters, legacies of armed conflict and insecurity in certain regions such as Aceh, and poverty, particularly affecting the needs of women and other marginalised groups such as people with disabilities. Although the Indonesian government has made significant investments in education, healthcare expenditure in Indonesia is among the lowest in the world when taking into account the population size and overall budget.2 There are large regional divides in terms of the level of human development depending on province (ranging from very high HDI to medium HDI)3. These inequalities are mirrored by the fact that some segments of the population, such as people with disabilities, continue to live in poverty, and have limited access to education, healthcare, jobs, public facilities, decision-making, and public transportation. Nationally, women’s rights groups argue that development strategies centering market liberalisation and foreign trade and investment, rooted in harmful historical patterns, have not delivered equitable benefits for the majority of people. Instead, while delivering economic growth that benefits a smaller segment of Indonesians, they have eroded labour conditions and escalated social and economic inequalities for the majority.

View Case Stories / Map

View Country Statistics

International Treaties/Conventions

Systemic Barriers in Achieving Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice

- Finance, Trade, and Investment Agreements

The colonial economy that was imposed on most of ...

- Unfair Labour Practices

Free trade and market liberalisation have resulted...

- Influence of Private Capital

Indonesia has been pursuing Public Private Partnerships...

- Rising Inequality and Decreased Social Protections

After the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997, income inequality...

- Land and Resource Grabbing

Indonesia is the host to many diverse ecosystems...

- Climate Crises

There is high vulnerability to climate change in Indonesia...

- Militarism and Conflict

Over recent decades, Indonesia has decreased its spending...

- Patriarchal Authoritarian Governance

The percentage of women in parliament in Indonesia has...

- Patriarchal Structures and Norms

There remain significant cultural and structural barriers...

Accountability

Sustainable Development: Structures of AccountabilityIn 2017, Presidential Law No. 59/2017 institutionalised the SDGs...

Recommendations

Women’s Priority Issues and RecommendationsReferences

- 1 Tsujino, R., Yumoto, T., Kitamura, S., Djamaluddin, I. & Darnaedi, D. (n.d.). History of forest loss and degradation in Indonesia. Land Use Policy, Vol. 57, 335-347. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0264837716305348

- 2 Asante, A., Cheng, Q., Susilo, D., Satrya, A., Haemmerli, M., Fattah, R. A., Kosen, S., Novitasari, D., Puteri, G. C. Adawiyah, E., Hayen, A., Mills, A., Tangcharoensathien, V., Jan, S., Thabrany, H. & Wiseman, V. (2023). The Benefits and Burden of Health Financing in Indonesia: Analyses of Nationally Representative Cross-sectional Data. The Lancet Global Health, 11(5), E770-E780. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(23)00064-5

- 3 BPS Statistics Indonesia. (2024). Capaian Pembangunan Manusia di Tingkat Daerah (Human Development Index: Achievements in Various Provinces). Indeks Pembangunan Manusia 2023 (Human Development Index 2023), Vol. 18, 27-28. https://www.bps.go.id/id/publication/2024/05/13/8f77e73a66a6f484c655985a/indeks-pembangunan-manusia-2023.html

Cambodia

Background

Cambodia is located in mainland Southeast Asia, with a population of 16.8 million people.1 It shares borders with Thailand, Laos and Vietnam, and is along the Gulf of Thailand. Cambodia is classified as a Least Developed Country (LDC)2 but has experienced significant economic growth in the past three decades, with its Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita increasing from USD 247.30 in 1993 to USD 1,759.60 in 2022.3

Agriculture comprises over 20 per cent of its economy and employs three million people,4 and industries such as textiles and garments, construction and tourism are also significant sectors. Although Cambodia has low historical and current carbon emissions, it is highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change. Erratic weather patterns such as floods and droughts threaten agricultural production and productivity as well as the supply of wood used for fuel. Further, climate change is exacerbating the impacts of deforestation.

Cambodia’s development trajectory has been impacted by colonisation, genocide and the ongoing impacts of three decades of armed conflict in the second half of the 20th century. It was colonised by France in 1863, and occupied by Japan during World War II like many other nations in the region. After independence in 1953, Cambodia was impacted by the Indochina Wars and subjected to bombing by the United States during the Vietnam War, killing hundreds of thousands of people. Under their rule, Khmer Rouge policies resulted in the deaths of almost 25 per cent of the Cambodian population from execution, starvation and violence. Today, Cambodia remains one of the most landmine-affected countries in the world. Four million unexploded landmines and munitions were removed between 1992 and 2018.5 Landmines continue to kill people in the country today.6

Since mid-2008, Cambodia has been affected by a combination of high oil and food prices as well as the global financial crisis.7 However, Cambodia’s economy also witnessed significant growth due to garment exports and tourism. Between 1998 and 2019, Cambodia’s economy grew at a rate of 7.7 per cent, which made it one of the world’s fastest-growing economies.8 The COVID-19 pandemic reversed some of these gains, by increasing unemployment and poverty. In addition, development gains have been impacted by factors such as variability in textile orders, decrease in tourism and declines in construction. These factors mean that there remain challenges to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).7

View Case Stories / Map

View Country Statistics

International Treaties/Conventions

Systemic Barriers in Achieving Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice

- Finance, Trade and Investment Agreements

In recent decades, particularly since the mid-1990s...

- Workers’ Rights

Although Article 36 of the Constitution of 1993 provides...

- Influence of Private Capital

Since the mid-1990s with liberalisation and privatisation...

- Land and Resource Grabbing

Conflicts over land and resources are a major barrier...

- Climate Crises

Cambodia has consistently been ranked amongst the...

- Militarism and Armed Conflict

The modern history of Cambodia has been deeply intertwined...

- Patriarchal Authoritarian Governance

A structural barrier to Development Justice in Cambodia...

- Patriarchal Structures and Norms

Traditional patriarchal gender norms and customs stand...

Accountability

Sustainable Development: Structures of AccountabilityWhen the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) were first adopted...

Recommendations

Women’s Priority Issues & RecommendationsReferences

- 1 World Bank Group. (n.d.). Population, total - Cambodia | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL?locations=KH

- 2 United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2024). Least Developed Country Category: Cambodia Profile | Department of Economic and Social Affairs. UN DESA Economic Analysis. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dpad/least-developed-country-category-cambodia.html

- 3 World Bank Group. (n.d.). GDP per capita (current US$) - Cambodia | Data. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=KH

- 4 Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries. (2023). Cambodia’s Agriculture Investment Framework [Powerpoint Slides]. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. https://www.fao.org/hand-in-hand/hih-IF-2023/cambodia/en

- 5 Ewe, K. (2023, August 15). How Buried Explosives Continue to Haunt Cambodia. Time. https://time.com/6304901/cambodia-land-mine-found-school/

- 6 Booth, R. (2024, April 22). Five people killed by unexploded land mines in Cambodia. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/asia/southeast-asia/cambodia-land-mines-mondulkiri-deaths-b2532645.html

- 7 SILAKA & Asia-Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development. (2017). Monitoring and Review of the Sustainable Development Goals & Development Justice. APWLD. https://apwld.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/SILAKA.pdf

- 8 World Bank Group. (2024, April). The World Bank In Cambodia - Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/cambodia/overview

- 9 SILAKA. (2017). Monitoring and Review of the Sustainable Development Goals & Development Justice. Asia-Pacific Forum on Women, Law and Development. https://apwld.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/SILAKA.pdf

Burma / Myanmar

Background

Burma/Myanmar is a country in mainland Southeast Asia with a population of approximately 55 million people. It borders Bangladesh, India, China, Laos and Thailand. Burma/Myanmar is a diverse country in terms of ethnicity, language, religion,and culture, with over 100 ethnic groups. It is rich in natural resources, including minerals, oil, natural gas and energy. It is also extremely vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, and was the second most affected country in the world between 2000 and 2019.1

Burma/Myanmar was colonised by Britain for 124 years between 1824 and 1948. Before the British colonisation, different ethnic groups lived independently and had their own leaders. The independence movement led by General Aung San brought together the different ethnic groups together to defeat the British colonial rule. The Panglong Agreement of 1947 was the first political agreement among different ethnic groups in Burma/Myanmar and granted powers of internal administration. However, political leaders failed to implement the Panglong Agreement, especially regarding equal inter-state treatment, right to secession, full autonomy and self-determination. The military seized power and expanded militarisation and repression, particularly against ethnic minority groups and revolutionary movements.

The post-colonial era has been marked by militarism, inter-ethnic conflicts and bitter power struggles between political parties, of which the 2021 military coup d’état is the latest. This most recent coup ended a ten-year period of democratic rule following the elections of 2010, in which the military junta was dissolved and civilian governments ruled, with successful elections in 2015. However, the military refused to accept the results of the 2020 election and forcibly attempted to seize power in February 2021. Protests against military rule have been met with severe repression and conflict has escalated into civil war. Extractive projects that displace communities have increased since the military junta took control. Political oppression and human rights violations by the military junta have become the norm. Meanwhile, protests for democracy and opposition movements continue.

As of 2024, 1.9 million people are internally displaced and millions more need urgent humanitarian assistance due to the ongoing conflict, natural disasters, the impact of the COVID-19 and political crisis in Burma/Myanmar. This crisis has increased the care work and responsibilities for women, many of whom are also active in human rights and civil disobedience work in opposition to military rule. Women-led civil society organisations in Burma/Myanmar continue to take on critical leadership roles in promoting human rights and highlighting the gender impacts of ongoing conflict.4 Communities in conflict-affected areas are being denied access to healthcare facilities, education and basic needs, exacerbating the humanitarian crisis. The COVID-19 pandemic was worsened by the hoarding of oxygen tanks and supplies by the junta, as well as the arrest of healthcare workers who were critical of the military rule and who participated in the Civil Disobedience Movement.5

View Case Stories / Map

View Country Statistics

International Treaties/Conventions

Systemic Barriers in Achieving Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice

- Finance, Trade and Investment Agreements

Even before the attempted coup and resurgence of armed...

- Influence of Private Capital

Crony politics is rampant in Burma/Myanmar, with the...

- Land and Resource Grabbing

Burma/Myanmar is rich in natural resources but has been...

- Climate Crises

Burma/Myanmar was the world’s second most affected country...

- Militarism and Armed Conflict

Communities in Burma/Myanmar have experienced decades...

- Patriarchal Authoritarian Governance

Burma/Myanmar is ruled by a combination of de facto actors...

Accountability

Sustainable Development: Structures of AccountabilityThe Ministry of Planning and Finance of the government of...

Recommendations

Women’s Priority Issues & RecommendationsBased on the specific challenges and problems faced by women

References

- 1 Lo, A., & Hoy, S. T. (2023, November 9). Conflicts intensify climate change risks in Myanmar. East Asia Forum. Retrieved June 29, 2024, from https://eastasiaforum.org/2023/11/09/conflicts-intensify-climate-change-risks-in-myanmar/

Malaysia

Background

Malaysia is a country located in Southeast Asia with two separate regions of Peninsular Malaysia and East Malaysia (located in Borneo). Peninsular Malaysia shares a border with Thailand, as well as maritime borders with Singapore, Vietnam and Indonesia. East Malaysia borders Brunei and Indonesia, and shares maritime borders with the Philippines and Vietnam. Malaysia is a Muslim-majority country and founding member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation (OIC). Its diverse, multi-ethnic population is half ethnic Malay, with large minorities of Chinese, Indian and Indigenous background. Malaysia is a megadiverse tropical country, but its biodiversity is increasingly being threatened by climate change as well as persistent land grabbing and deforestation.

Malaysia, with historically different Malay sultanates, was severely impacted by centuries of colonisation by the Portuguese, Dutch and British empires from 1511 onwards, and then occupied by Japan in World War II. Under the British colonial economy, Chinese and Indian workers immigrated to Malaya, Malaysia’s former name, to work. Malaya became an independent state in 1957, united with North Borneo, Sarawak and Singapore in 1963 to become ‘Malaysia’ and then Singapore was expelled from the confederation in 1965. Its contemporary economic development model is increasingly centred on market liberalisation and free trade at the expense of labour rights and the environment. Malaysia retains some archaic, repressive colonial-era laws that undermine the rights to free expression and speech.

Malaysia faces many barriers to Development Justice and sustainable development, including with regards to its neoliberal development model, governance and legal system, human rights and environmental protection. Malaysia has comparatively low levels of ratification of international treaties and notably has not ratified the International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, despite the fact that this Convention has been ratified by 179 other countries. Racial discrimination is embedded within Malaysian policy and its constitution, privileging ethnic Malays through policies of positive discrimination. Advantages include preferential treatment in higher education, while there is racial discrimination in areas such as employment, finance and housing. Despite theoretical advantages to native communities in Sabah and Sarawak and First People of Peninsular Malaysia, in practice, these communities are left behind and also face marginalisation. Realising the aspirations of leaving no one behind would therefore require an overhaul of the current political and socioeconomic realities in Malaysia, in particular in relation to aligning with international human rights standards.1

View Case Stories / Map

View Country Statistics

International Treaties/Conventions

Systemic Barriers in Achieving Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice

- Finance, Trade and Investment Agreements

Since the mid-1980s, the development model of Malaysia...

- Labour Rights of Migrant Workers

There are 2.2 million documented migrant workers in Malaysia...

- Influence of Private Capital

Malaysia has been pursuing Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs)...

- Land and Resource Grabbing

Malaysia is one of the most biodiverse countries in the world...

- Climate Crises

Due to its high level of biodiversity, Malaysia is vulnerable...

- Militarism and Armed Conflict

In 2023, Malaysia’s military expenditure reached 3.899 billion...

- Patriarchal Authoritarian Governance

The context in Malaysia is characterised by restrictions on...

- Patriarchal Structures and Norms

There are persistent gender inequalities in Malaysia...

Accountability

Sustainable Development: Structures of AccountabilityIn the initial planning for implementing the Sustainable Development...

Recommendations

Women’s Priority Issues & RecommendationsBased on the specific challenges and problems faced by women and

Vietnam

Background

Vietnam is a coastal nation located on the eastern coast of the mainland portion of Southeast Asia. As of 2023, its population is estimated to be hovering around the 100 million mark, making it the fifteenth most populated country in the world.1,2 It shares borders with China, Laos and Cambodia, and maritime borders with Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia and Malaysia. Vietnam has a diverse climate and topography of hills, mountains, deltas and coastline, which make it rich in natural resources and the 16th most biodiverse country in the world. It has fertile soil, diverse flora and fauna and caves, and approximately 39.7 per cent of the country is forested, with 85,000 hectares of primary forest.3

Vietnam experienced successive armed conflicts, partition and military occupation throughout the 20th century, with devastating impacts on the population. The Japanese invasion of Indochina, including Vietnam, caused a famine that killed up to two million people. The invasion of the United States in support of South Vietnamese forces against North Vietnam – known as the ‘American War’ in the country – also killed millions of Vietnamese civilians as well as soldiers on both sides of the conflict. The war continues to have lasting impacts on Vietnam’s people and environment, such as unexploded ordnance and the effects of deadly chemicals used during the war.

In recent years, following the reunification of Vietnam and the end to armed conflicts, its economy has rapidly developed into a middle-income nation, leading many to remark on its trajectory as a regional success story. Vietnam has made progress towards reducing poverty and hunger, achieving universal primary education, universal electrification and promoting gender equality. Millions of people were lifted out of poverty starting in the 1990s, and in one decade, from 2010 to 2020, poverty declined from 16.8 per cent to 5 per cent, according to the World Bank.4 However, these gains have not been equitable with some communities such as ethnic minority groups maintained in a persistent state of poverty, leaving more progress needed for the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).5 Many households overall are still financially and economically insecure and face barriers in the middle class, even if they are no longer at risk of extreme poverty.6

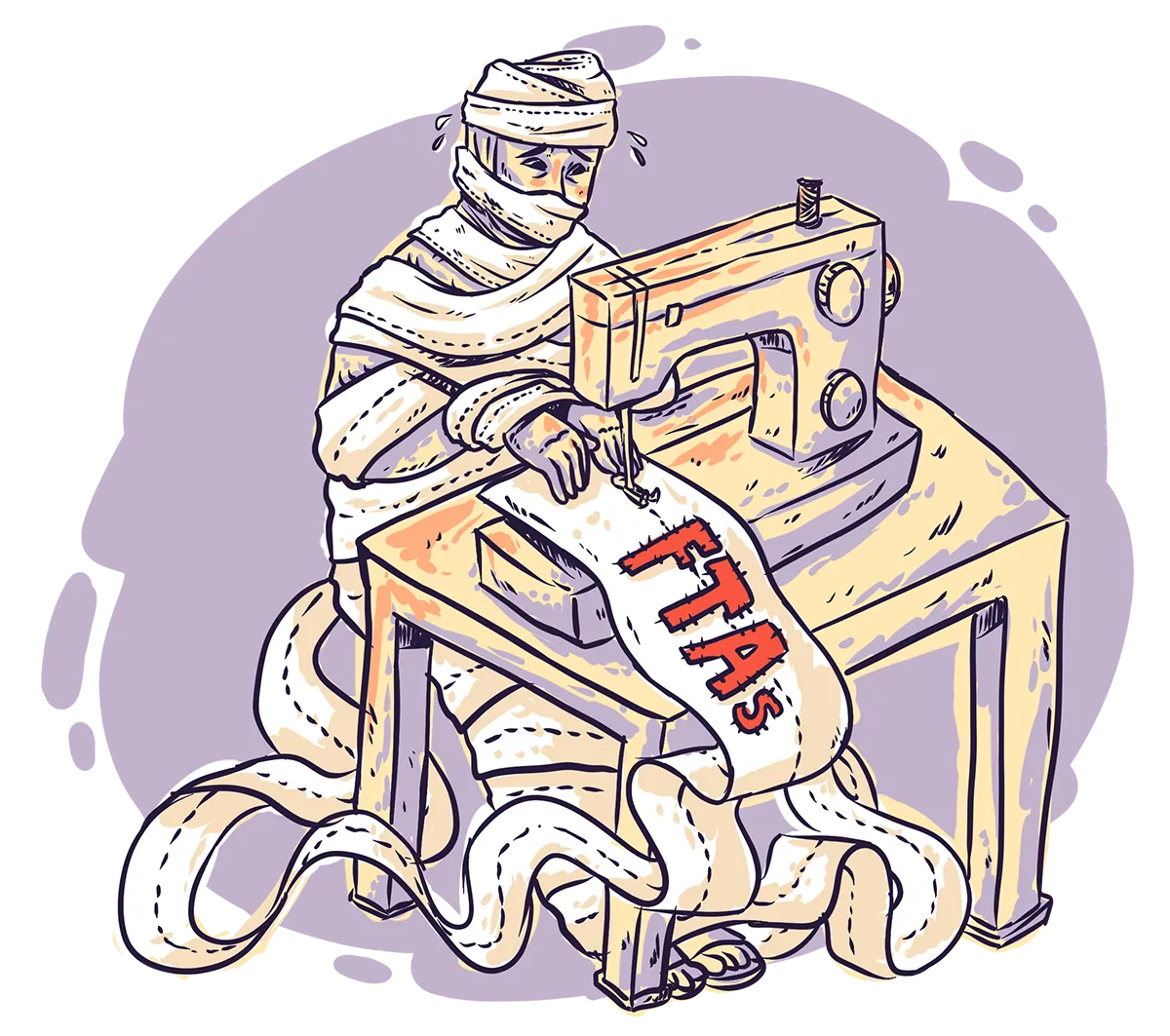

Recent years have also witnessed significant shifts in Vietnam’s economic model. Vietnam is ruled by one-party communist rule, but has been embracing a more capitalist free market model, resulting in economic growth but also a rise in inequality. It has been increasingly pursuing Free Trade Agreements (FTAs) and foreign investment as well as a reduction in the agricultural sector through policies of urbanisation and industrialisation.7 Vietnam’s rural population has declined from 85 per cent in 1960 to 60.5 per cent in 2023.8 As of 2022, 11.9 per cent of Vietnam’s economy is in agriculture, 38 per cent in industry and 41 per cent in services, proportions which have remained relatively stable over the prior decade with some decline in agricultural share.9 However, these realities are threatened by the increasing impacts of the climate crisis. Natural disasters such as tropical cyclones and typhoons, which are increasing in frequency, pose a significant risk to Vietnam’s environment, economy and population.

View Case Stories / Map

View Country Statistics

International Treaties/Conventions

Systemic Barriers in Achieving Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice

- Finance, Trade and Investment Agreements

Vietnam occupies a central position in Southeast Asia, with...

- Influence of Private Capital

Government partnerships with the private sector are growing...

- Land and Resource Grabbing

In the 1980s and 90s, land laws and agricultural transformation...

- Climate Crises

Vietnam is heavily vulnerable to diverse natural disasters...

- Militarism and Armed Conflict

Throughout the 19th and 20th centuries in particular...

- Patriarchal Authoritarian Governance

Although there is still more progress to be made in terms...

- Patriarchal Structures and Norms

Patriarchy dominates the public and private spheres in Vietnam...

Accountability

Sustainable Development: Structures of AccountabilityIn May 2017, Vietnam’s National Plan for Implementation of Agenda...

Recommendations

Women’s Priority Issues & RecommendationsAmong the many challenges that Vietnam faces to achieving the SDGs

References

- 1 Vietnam General Statistics Office. (n.d.). Socio-economic situation in the fourth quarter and 2023. https://www.gso.gov.vn/en/data-and-statistics/2024/02/socio-economic-situation-in-the-fourth-quarter-and-2023/

- 2 Worldometer. (n.d.). Vietnam Population (2024). https://www.worldometers.info/world-population/vietnam-population/

- 3 UN-REDD. (2021). Vietnam Forest Facts and Figures, 2005. https://www.un-redd.org/sites/default/files/2021-10/Vietnam%20Forest%20Facts%20and%20Figures.pdf

- 4 World Bank Group. (2022, April 28). 2022 Vietnam Poverty and Equity Assessment – From the Last Mile to the Next Mile. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/publication/2022-vietnam-poverty-and-equity-assessment-report

- 5 World Bank Group. (2022, April 28). 2022 Vietnam Poverty and Equity Assessment – From the Last Mile to the Next Mile. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/vietnam/publication/2022-vietnam-poverty-and-equity-assessment-report

- 6 World Bank Group. (2023). Poverty & Equity Brief: East Asia and the Pacific - Vietnam. https://databankfiles.worldbank.org/public/ddpext_download/poverty/987B9C90-CB9F-4D93-AE8C-750588BF00QA/current/Global_POVEQ_VNM.pdf

- 7 Pham Thi, N., Kappas, M. & Faust, H. (2021). Impacts of Agricultural Land Acquisition for Urbanization on Agricultural Activities of Affected Households: A Case Study in Huong Thuy Town, Thua Thien Hue Province, Vietnam. Sustainability. MDPI. https://www.mdpi.com/2071-1050/13/15/8559

- 8 World Bank. (2024). Vietnam - Rural population. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?locations=VN

- 9 O'Neill, A. (2024, July 4). Vietnam: Distribution of gross domestic product (GDP) across economic sectors from 2012 to 2022. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/444611/vietnam-gdp-distribution-across-economic-sectors/

Thailand

Background

Thailand is a nation located in the centre of Southeast Asia, and home to 71.7 million people, making it the third most populous country in Southeast Asia and the 20th most populous country in the world. Thailand shares borders with Burma / Myanmar, Laos, Cambodia and Malaysia, and shares maritime borders with Vietnam, Indonesia and India. It is the second-largest economy in Southeast Asia, and is a newly industrialised economy.

In the past five decades, Thailand has transitioned from a low income to a middle income country, shifting from an agricultural economy to one centred on export-led growth and fueled by other sectors such as tourism. Its economy grew significantly before the Asian Financial Crisis in 1997 but has had moderate growth since.1 It is classified as an upper middle income country as of the early 2010s; poverty – as measured according to the national poverty line – has also declined substantially, from nearly 60 per cent in 1990 to 7 per cent as of 2022.2 Poverty reduction is slowing, however, with some increases in poverty in recent years.3 However, national social and economic developments in the past thirty years have not equally distributed the resources, wealth and opportunities of this growth, resulting in significant income disparities and inequalities. Some of the economic progress has come at the expense of the environment, through exploitation of natural resources, and alongside violations of human rights, workers rights and community rights, as explored in the different sections of this profile. These elements pose a significant barrier to Development Justice and the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

In Southeast Asia, Thailand, formerly under the name of Siam, is the only country in the region that was not colonised by foreign powers, and is indeed one of only a few countries in the world that evaded foreign colonisation. However, it was still impacted by imperialism, including through uneven and unequal treaties and trade relationships. Now for nearly a century, Thailand has alternated between periods of military rule and democracy, experiencing recent military coups in 2006 and 2014. There have been thirteen successful coups since the revolution and establishment of the constitutional monarchy in 1932, and there have also been over 20 different constitutions or political charters during this period.4 The current constitution has been in effect since 2017. A recent wave of protests took place in 2020 and 2021, which included unprecedented demands for monarchy reform, constitutional reform and the dissolution of parliament, as well as more space for democratic governance. These protests were met with intimidation, arbitrary detention, censorship and other forms of repression. Thailand is also affected by the ongoing civil war between the military junta and opposition forces in Burma/Myanmar. Many refugees have fled into Thailand, and Thailand is also the home to many migrant workers from the region.

Thailand has a subtropical to tropical climate and has diverse ecosystems in different regions of the country, including mountains in the north, hills, plains and a long coastline. Because of this, it has a high vulnerability to climate change, and it was ranked as the ninth most affected country in terms of human impacts and economic losses from disasters between 2000 and 2019.5 Floods are the greatest risk facing Thailand in terms of climate hazards.6 It is one of the top ten most affected countries by floods in the world, exacerbated by an increase in rainfall patterns and higher temperatures. Sea level rise is projected to potentially force the internal displacement and relocation of 12 million people by 2050. Despite this, Thailand’s greenhouse gas emissions have substantially increased over the past decade or more,7 with 3.7 metric tons per capita of emissions.8

View Case Stories / Map

View Country Statistics

International Treaties/Conventions

Systemic Barriers in Achieving Women’s Human Rights and Development Justice

- Finance, Trade and Investment Agreements

Neoliberal globalisation has enabled the proliferation of...

- Workers’ Rights and Labour Standards

The treatment of migrant workers in Thailand is characterised...

- Influence of Private Capital

In Thailand, there are a number of ways in which corporations...

- Land and Resource Grabbing

Widespread income inequality in Thailand is mirrored by...

- Climate Crises

Thailand faces many threats as a result of rising sea levels...

- Militarism and Armed Conflict

Thailand has experienced sporadic coups since the...

- Patriarchal Authoritarian Governance

Women are often systematically excluded from political power...

- Patriarchal Structures and Norms

When disaggregated by gender, Thailand’s Human Development...

Accountability

Sustainable Development: Structures of AccountabilityThe systemic barriers to achieving sustainable development in...

Recommendations

Women’s Priority Issues & RecommendationsReferences

- 1 Government of Thailand and the OECD. (2022, January 8). Thailand’s development trajectory: Past and future strategies. OECD Investment Policy Review of Thailand. OECD iLibrary. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/c4eeee1c-en/1/3/2/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/c4eeee1c-en&_csp_=863e6fff88efb4d2acb683294e900838&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=book#wrapper

- 2 Government of Thailand and the OECD. (2022, January 8). Chapter 2 Thailand’s development trajectory: Past and future strategies. OECD Investment Policy Review of Thailand. OECD iLibrary. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/c4eeee1c-en/1/3/2/index.html?itemId=/content/publication/c4eeee1c-en&_csp_=863e6fff88efb4d2acb683294e900838&itemIGO=oecd&itemContentType=book#wrapper

- 3 World Bank Group. (2024, April). Thailand Overview: Development news, research, data. World Bank. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/thailand/overview

- 4 Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand. (2017). https://web.parliament.go.th/assets/portals/61/filenewspar/61_1059_file.pdf

- 5 Kingdom of Thailand. (2022). Thailand’s Fourth Biennial Update Report. UNFCCC. https://unfccc.int/sites/default/files/resource/Thailand_BUR4_final_28122022.pdf

- 6 World Bank Group & the Asian Development Bank. (n.d.). Climate Risk Country Profile: THAILAND. Climate Change Knowledge Portal. https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/sites/default/files/2021-08/15853-WB_Thailand%20Country%20Profile-WEB_0.pdf

- 7 Banerjee, N. (2020, December 30). Thailand’s Carbon Dioxide Emissions Have Significantly Increased Over the Past 10 Years. Climate Scorecard. https://www.climatescorecard.org/2020/12/thailands-carbon-dioxide-emissions-have-significantly-increased-over-the-past-10-years/

- 8 World Bank. (n.d.), CO2 emissions (metric tons per capita) - Thailand. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.ATM.CO2E.PC?locations=TH

India

Background

India is the world’s fifth largest economy and as of 2023 has become the most populous country in the world, home to over 1.4 billion people.1 This means that a sixth of people in the world live in India, making it critical for the achievement of Development Justice and the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).